Yee-haw! We do Westerns now, pardner!

OK, enough of that.

We’re breaking form from your regular (as of the past month) Indie Triple Play to bring you two reviews of comics of a similar bent, as Matthew Lazorwitz reviews Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips’ latest OGN, Pulp, and Will Nevin looks at the second issue of Chris Condon and Jacob “Son of Sean” Phillips’ That Texas Blood, both from Image.

Pulp

Writer: Ed Brubaker, Artist: Sean Phillips, Colorist: Jacob Phillips, Publisher: Image

I’ve written extensively about the creative team of Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips and their varied colorists, and new work from this team is something I look forward to with bated breath. “Pulp” is the closest thing to a Western that Brubaker and Phillips have ever done and probably will ever do, and it is, in places, a Western. But it’s also a noir, a genre the two are most associated with. It’s the story of a man at the end of his life trying to make good for the people he cares about, and the price he is willing to pay in the end to do it.

Max Winter is living in New York City in 1939 and makes a living writing for the pulps, the magazines that were what comics sprang from in many ways. Specifically, Max writes Westerns, the stories of the Red River Kid and his partner, Heck Randal. What no one in his life then realizes is that these stories are loosely based on reality, when Max and his best friend, Spike, were honest-to-God outlaws in the late days of the Old West.

But the money isn’t great, Max is getting older, and he wants to provide a happy ending for his younger wife, Rosa. And when Max finds his heart is giving out, he starts to plan a robbery like he did in the old days. Now older and alone, he is quickly found out by Jeremiah Goldman, one of the Pinkerton agents who hunted him in the old days, and who was looking for him again to offer him one last big score: a chance to steal a crate of money from The Bund, the American face of the Nazi Party. But as with any noir, the heist is not what our lead expects, and things go from bad to worse, leading to a brutal conclusion that could take place in a New York bar or a Texas saloon and feel just as at home.

“Pulp” treads the line between the noir and the Western deftly. Readers are shown bits of the Red River Kid pulps Winter is writing, and bits of his past as an outlaw, but the majority of the story is set in the “present” of 1939. And while these are two distinct genres, the story reminds us how similar they are. They’re both stories of lawless times, with men who stretch the law to do right, or what they view as right. And in many, if not most cases, the endings are bloody and the good guy doesn’t always walk away.

Winter is a different kind of protagonist than we’ve seen in the Brubaker and Phillips books before. Brubaker hasn’t written an elderly central figure before; most of his leads are middle-aged to twenties, either starting out their criminal careers or looking for that score to set them up for life. Max is more haunted than most of these leads, and while he is a killer, he’s more reformed than most, and more sympathetic.

It also helps that Max is working against Nazis. Brubaker builds up the fact that we’ll be dealing with this slowly. Max tries to stop an anti-Semitic attack near the beginning of the book, only to have a heart attack after getting a beating, and then sees a newsreel about the rise of Hitler, which also causes him to suffer a minor cardiac episode. And when Goldman comes to him with the pitch for the robbery, well, I don’t think any reader will shed tears for the collateral damage.

Brubaker is absolutely calling out the fact that facism has existed in America since its rise in the ’30s and ’40s, even if it didn’t gain the same power as it did in Europe, and does not disguise the anti-Seimitism that was so prevalent at the time, and is not far away today. This book was originally due out in May, before the industrywide shutdown, and while it’s not like we haven’t seen fascistic tendencies in recent American politics before the past few months, the book takes on new resonance when held up against the news of the moment.

The theme of the book — being haunted by your past and still trying to do the right thing — spoils the reader’s thrill at seeing the bad guys gunned down in the end. Max himself has some insight into being a killer, and in the bloodsoaked, “Taxi Driver”-esque conclusion, he admits he is a killer and a monster, even if he is killing monsters himself. Brubaker isn’t making a false, good-people-on-both-sides equivalency. But Max, and maybe the writer himself, is haunted by the fact that it’s a world where it takes a monster to survive, and while you can hope for a better world, it takes more than that to make it real.

Sean Phillips’ art is as astounding as ever, well-researched in both of its eras, with great character design. None of these characters are archetypal comic book heroes, nor are they the expected gritty noir Sam Spade types. Max and Jeremiah are old men, and their age can be felt in every panel they appear in.

What helps make Phillips’ art sing are son Jacob Phillips’ colors. The sequences in the present are colored mostly realistically, with a bit of heavy grays mixed in, while the flashbacks and pulp sequences are colored with sepias and oranges, the only striking color being the Red River Kid’s red shirt. During the heist at the Bund headquarters and the finale, the two sets of coloring blend together, drawing a clever visual parallel between the two eras.

“Pulp” is a story about a man facing down his sunset years, and setting his accounts to right. It is a vivid tale of the late 1930s, as the world stood on the precipice of a great conflict, and sees one man fighting a small battle. In the end, he faces evil and pays the price. It’s an astounding work, and something for the lover of the Western, the noir, the pulp or just great graphic storytelling.

That Texas Blood #2

Writer: Chris Condon, Artist: Jacob Phillips, Publisher: Image

The lifecycle of the comic book reader (journalist?) is this: begin with capes and tights and heroes (pick your Big Two titan here, they are fungible for these purposes); become disillusioned with said heroes and their crises and their constant churn of unchanging, unmoving stories; move on to independent books with an infinitely more diverse universe of stories, voices, characters and feelings; die with approximately 1,856 unread comics.

These are the immutable laws of comic book reading.

If you’re anything like me — on the backside of that curve and eyeing all those Vault books you swear you’ll get to while you can’t be bothered to even learn anything about Empyre or whatever the hell else Marvel is doing — then “That Texas Blood” will hit like a warm pair of slippers and a hot cup of coffee on a cold morning. It is the quintessential non-comic comic book, a slow-moving, brooding thing content to amble at its own pace.

And good for it.

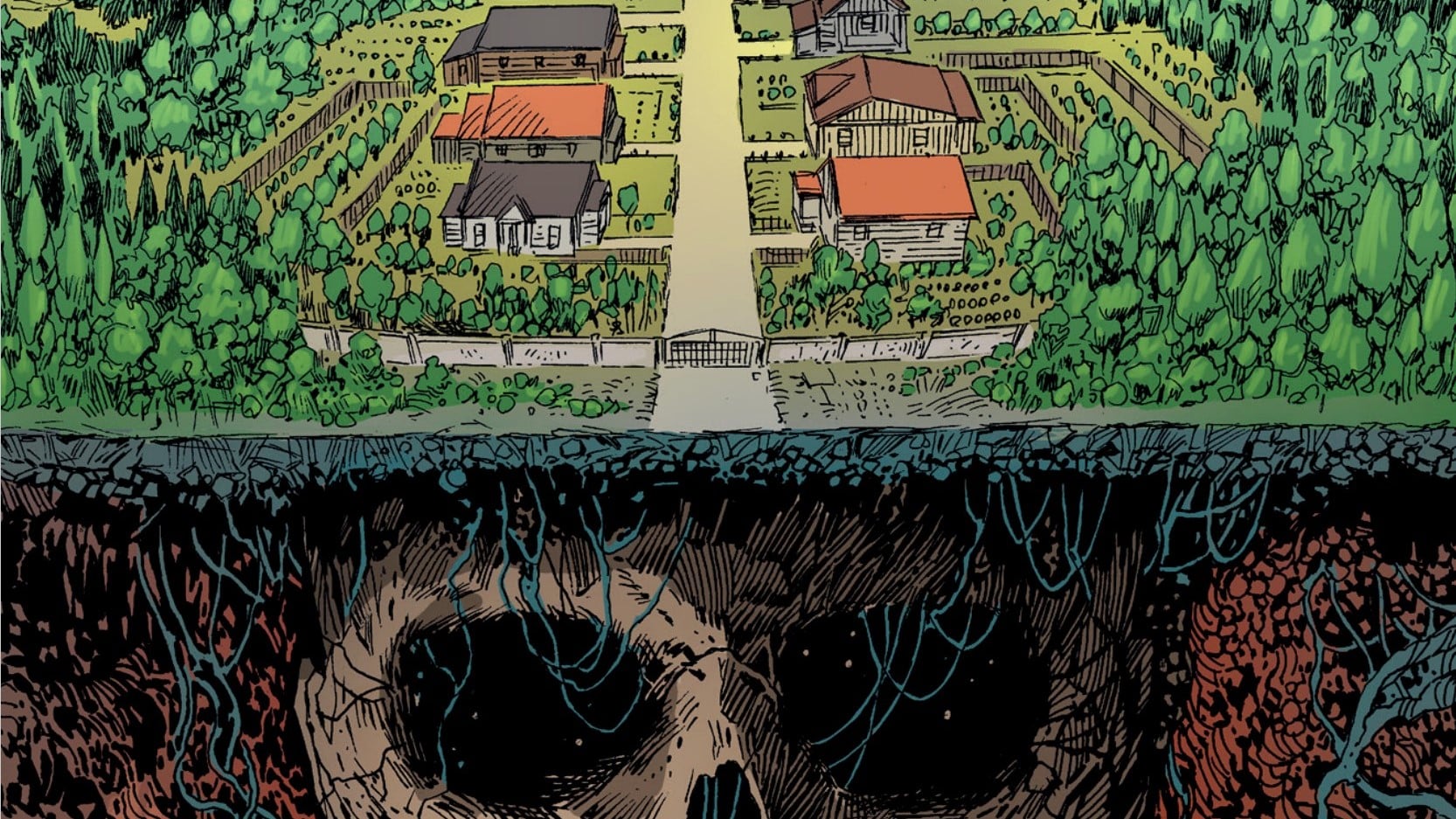

In the first issue, we meet Sheriff Joe Bob Coates of Ambrose County, Texas, a newly minted 70-year-old not yet ready to sink into the dry ground. We ride around with him as he patrols, with every line so skillfully placed on his face by artist Jacob Phillips, each one telling a story of age and creeping regret. And while #1 ends with … well, a cliched joke I’m above making … the issue as a whole has a positively Seinfeldian vibe in that it’s not creating some serious emergency for Coates to cowboy his way through. It’s a debut issue that exists for you to soak in, to breathe up, to get that Texas grit under your fingernails and in your boots.

Decompressed?

Friend, that ain’t the half of it.

In this second issue, there is less Joe Bob (boo) and more story (hiss), but these are in truth necessary evils if Phillips and writer Chris Condon want to continue to sell books since perhaps only I would read 30 issues of Joe Bob riding around in his car and thinking about all the bad things in his life. Alas, no, this issue introduces us to Randy Terrill, a former Ambrose County boy who got out and made somethin’ of hisself, only to have to return to this dry backwater town upon the murder of his brother Travis. We don’t learn much about Randy — only that he and his brother aren’t exactly remembered fondly — but we still got time to flesh out what is otherwise a trope.

There’s no denyin’ this book is pretty as hell — I think Joe Bob’s moustache and facial expressions and the facial expressions of his moustache are the stuff of Eisners — and the ambiance and mood don’t get much better. It’s hard to know now what this book has to say on whatever big themes Condon and Phillips hope to hit, but right now, “That Texas Blood” could be “Southern Bastards” minus the football and scumbaggery of half the creative team.

So far, it’s that good.