I’ve never been drawn to war stories. There’s an impenetrable incomprehensibility that I’m not often able to move past. It’s like our inability to comprehend large numbers but applied to extreme emotional settings of violence and trauma. When faced with such powerful, loud, visceral or violent imagery, I often just … dissociate. Many creators, especially those I admire, don’t create for anybody except for themselves, but the dilemma of depicting hyperintense events or experiences in ways the audience can absorb is one I think about a lot and one that Lost Soldiers is able to overcome.

Crafted by Aleš Kot, Luca Casalanguida, Heather Marie Lawrence Moore, Aditya Bidikar and Tom Muller, Lost Soldiers traverses the landscape of war fiction in ways worth exploring. Despite having a profound impact on the comics medium, war comics aren’t talked about often beyond a new Garth Ennis release. The Silver Age was filled with war comics. From Our Army At War to Blazing Combat to Star-Spangled War Stories to Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos, there was no shortage of creators looking to portray the action, violence, glory, patriotism, suffering, absurdity and bigotry war has to offer, but few have captured its all-consuming nature in the way Lost Soldiers does.

‘It never leaves you, not really’

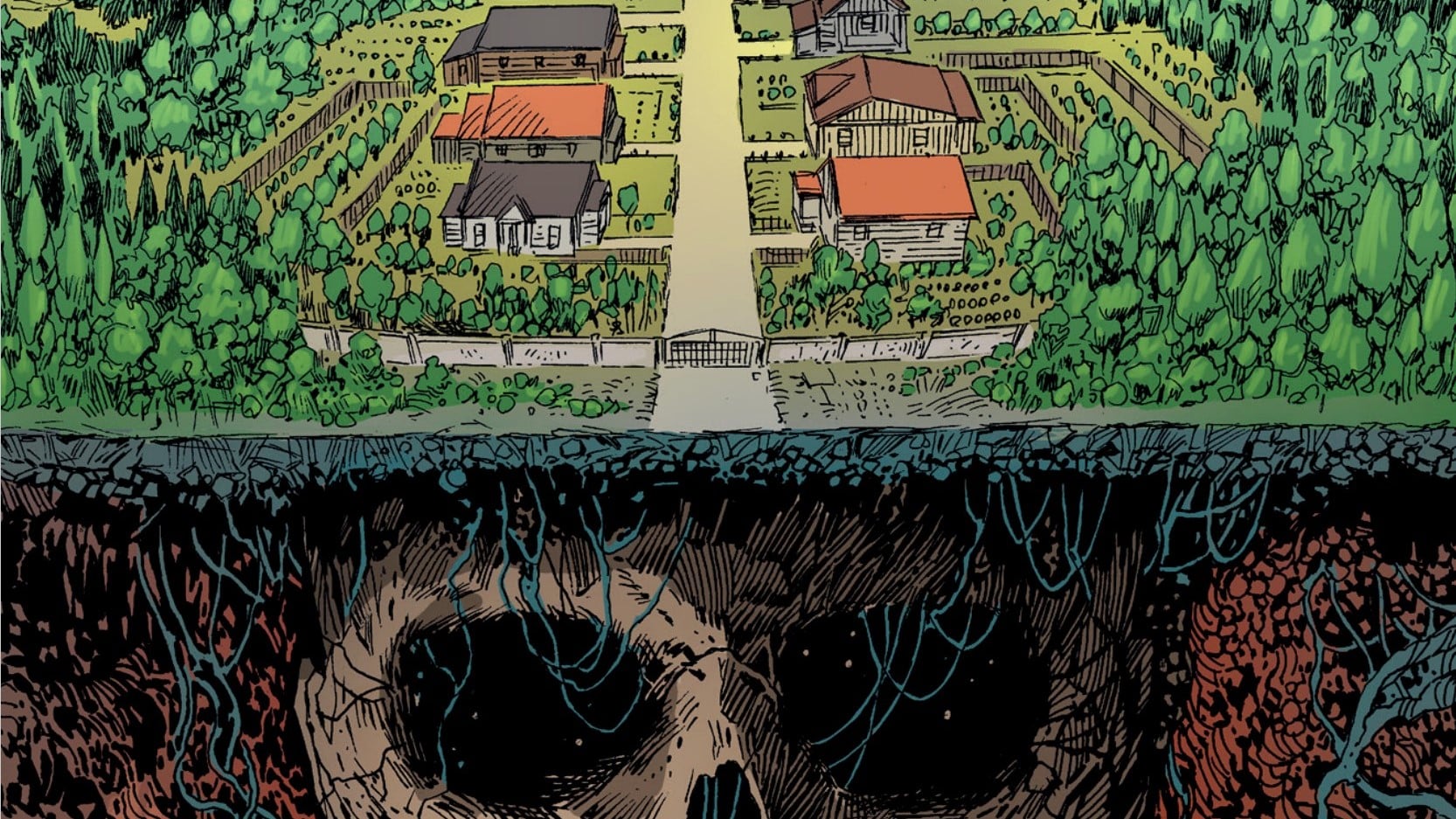

The book begins with two vital quotes. Quotes used in comics are often done simply to achieve an effect. Whether it be to sound smart by referring to something obscure or to provide a new twist on a classic line and leave the reader to discover the connection, quotes seldom say anything new or become part of the work itself. This is not the case with Lost Soldiers, which begins with a quote from bell hooks’ The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love and a quote from Gloria Evanɠelina Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Frontera. Both not only inform but provide invaluable context before the book begins. Even before we get to what the quotes actually say, their very presence is enough to convey that intersectionality is essential to this book. Lost Soldiers isn’t here to be another universal war comic. It’s here to examine war’s intersections with gender and racial identity. It begins from a place of dissecting the inner workings of masculinity and war; that war is a ritual which perpetuates an emotionally suppressive, patriarchal view of masculinity and that its glorification and perceived necessity cause men to become willing participants in a practice that ultimately kills a part of them. It begins by stating that when your home and a battlefield become the same thing, your entire life becomes an infected open wound.

From a craft perspective, Lost Soldiers opens with a fascinating interplay between density and noise. The density, the amount of information for the reader to take in on the opening pages is astounding. The narration is prose-like, drawing upon powerful imagery of the dead. The team cleverly saves the most powerful images for these captions, I think because they realize that no matter how talented a team like Casalanguida and Moore may be (and they are phenomenal), no one is going to draw “the sound of a throat being opened like a plastic curtain packed with blood and air pockets and wrapped tight” better than a reader can imagine such a visceral image in their own mind. It’s beautifully described and paints a different picture from the bloody trail we see leading to a dying soldier. There’s a delicate balance, and both lead to the idea that war swallows all, until only the “memory of the mud” remains.

The flashbacks are equally dense and quiet. The first page showing Vietnam in 1969 opens with a beautiful night sky and landscape quickly filled with dialogue about heroes and John Wayne vs. Superman. There’s a pervasive atmosphere of nervousness. The word balloons fill the space between the soldiers because talking is all there is to do while keeping watch and because silence is too nerve-wracking. You can tell from their expressions that everyone is always on edge. War has already consumed the silence, the peace and the comfort.

The present is set during a special infiltration operation near Juarez, Mexico. Kowalski and Hawkins are still there 40 years later. War has consumed their entire lives, transformed them or, as is appropriately portrayed when Kowalski takes a handful of pills with a swig of coffee, forced a red pill down their throats. They’ve never stopped fighting. They probably don’t know how. They probably still feel the pain.

Lost Soldiers is a difficult series to read. Not just because of the jarring imagery but because of how difficult it can be to relate the captions to what’s happening on the page. The graphic detail described with prose-like narration is both severely detached from the mostly conversational and expository events that appear before us and absolutely necessary.

But what does all this have to do with the lenses presented at the beginning of the issue? Everything. There are only men in the first issue. We see young boys become soldiers. We see Kowalski tell Hawkins to kill his emotions. Bury them. Suffocate them. You see, when we next travel back to Vietnam, Berg is dead, full of bullets as Hawkins stands over him. There’s a phenomenal texture to the moment and the book itself. All of the grime, blood, metal and utter shock are on display, overlaid by phenomenal flashes of red and green that bring a surreal element to it all as soldiers almost step out of their skin to become one with the violence around them. Whether it be in the past or the present, the wear and fatigue are always present. After the battle is over, those flashes of red and green, accompanied by images of all the trauma Hawkins has seen and experienced, stay with him. He is not OK, and Kawalski tells him to eat, to hold on to that hate. Kowalski is telling Hawkins to eat and let himself be eaten. It’s not just figurative either, as we find that prostate cancer is eating away at Hawkins 40 years later.

Lost Soldiers is rooted in character. It’s defined by character. Its characters are rich and deep, but not developed. Rather, they are stunted, their growth, maturity and emotions cleaved and consumed by the sharp teeth of war. The perpetual cycle is made equally clear by the fact that Hawkins and Kowalski are still in this life, leading more young soldiers to the same half-deaths and open wounds that defined their existences. The battlefield became their place of comfort. It became their home, and the open wound of their lives swelled until war infected and occupied it all. In the aftermath and the in-between, all they have is each other and themselves. It’s often filled with blank stares and directionless mutterings. The traumatic and haunting nature of it all is reminiscent of Delroy Lindo’s monologue in Da 5 Bloods, filled with aimless and all-encompassing guilt, resentment and rage. In that respect, the creators all but ensure at least one of the many messages Lost Soldiers has to offer reaches the reader.

The first issue proposes an interesting question: “Which soul disappears first? The soul of the boy or the soul of the first boy the boy kills?” A cynic might ask why it matters; after all, they’re both dead, but one still walks. The boy is a zombie, still moving and able to infect others, and once infected, there’s no way out. Lost Soldiers #1 ends with fictional newspaper clippings reporting the American military industrial complex’s involvement, official and unofficial, in Mexico, and the lives it has cost on both sides. It criticizes the powerful but arbitrary lines that have been drawn, both moral and physical. Finally, written on a napkin, is a letter warning a captain about the behavior of Burke, a physically strong, reckless and angry soldier whose decision-making killed a lot of soldiers. When this note was written is a mystery. What it illuminates is that all of the visceral trauma and emotions portrayed are systemic and not isolated to the characters on the pages.

‘Irreversible’

Lost Soldiers #2 begins with a quote from Sarah Kane’s Blasted. It’s a pretty brutal one, only a few lines, from an absolutely guttural play, and it speaks to the unspeakable horrors soldiers can become desensitized to during war, the atrocities soldiers may commit just to feel anything at all after having many of their emotions eaten away by violence, and the permanent consequences of war’s consumption.

We see tension, even when levity is being portrayed. Despite the soldiers in the opening scene in Vietnam being on a scouting mission, with potential danger lurking through the trees, the soldiers are bonding. I suppose this speaks to an idea that men can be at their most vulnerable during times of intense stress. This is the first time Vietnam is … bright. Moore’s greens are lush, the lighting impeccable and as Kowalski cracks a joke, the barest hints of levity poke through the trees.

This is severely contrasted with the nighttime operation in Juárez during the present. Four black cars bathed in light move under a pitch black night sky as death monologues about the order it has. Kot’s captions are a mix of prose and poetry as descriptions of a town at night invoke images of a carried out massacre. Quiet is mixed with deadly. Thought-out is confused with safe. Order is confused with clean.

There’s a lot of messiness here. You look at Kowalski and Hawkins, two people who must have a relationship after serving in some capacity together for 40 years, but who really knows. Some men, many soldiers, don’t open up easily, and just because one helps another out once doesn’t mean they’re friends. Kowalski makes that clear to Hawkins in Vietnam. Casalanguida and Moore do a great job bringing us in and out of settings. In one moment, the rain is falling so hard that the soldiers’ flimsy shelter appears to be melting. In the next, moments of vulnerability between soldiers are made to stand out by depicting them in front of a blank background with slightly yellower word balloons and thicker outlines. It’s these details that elevate a series like this to the next level.

It’s interesting that Kot talks about the idea of operations after dark or of sneaking behind enemy lines as creating nothing where there was something, mentioning that “The thing about shooting a person is you punch the void into them with a bullet.” The imagery seems to imply that the bullet is simply the delivery mechanism. The destruction is all too human, a sentiment that is echoed throughout the series. But there’s a certain absence to the metaphor, a lack of consumption. Punching a void is not the same as consuming what was there. Instead it feels like more of a simple substitution, an erasure. But shouldn’t there be an idea of ownership? Even if it is war itself, something is taking what was there, but it did exist. It’s a curious difference. Is there someone to blame?

For Kowalski and Hawkins, there is. It’s Burke, who led innocent men to their deaths, took advantage of Kowalski while he was hallucinating and 40 years later appears to be on the side of the cartel. Just like the first issue, the narrator repeats, “No, no, I don’t want to” over and over again. The narrator could easily be Kowalski’s dissociated mind, as it is strongly implied that Kowalski is raped by Burke during a period where he is ill and hallucinating, but still salient enough to say no. Hawkins, who looks after Kowalski, goes outside for a smoke, probably aware of what’s about to happen, but too scared to do anything about it as he buries his face in his hands. What actually happens during that flashback is completely depicted through visual storytelling. There are subtleties that line up perfectly with Kot’s poetic description of the mind leaving the body during trauma. The panel layouts showing Hawkins’ shame or grief in the past fit so well with the layout showing Kowalski’s shock and rage in the present. It is all at once a satisfying and horrific climax to only the second issue amplified by the bangs of gunfire. It is only after the primary story ends and you’re staring at the redacted backmatter showing parts of Burke’s military history that it can all sink in. It’s only then that the monster of war is really given a face. They’re all victims. They’re all perpetrators. They’re all sick. They’re all part of the problem. When everyone’s to blame, when institutions and constructs are to blame, are individuals to blame also? Even when the mind forgets, the impact of actions and the destruction of war never leaves. It is permanent, unspeakable and irreversible.

‘Shell shock’

Lost Soldiers #3 begins by quoting a scene from Lynch and Giffords’ Lost Highway. Lost Highway is a complicated movie about many things, the most applicable of which is dissociation and transformation, and the scene being quoted muddles reality, possibility and the mind all in one. Yet Lost Soldiers #3 does not begin with such muddling. It begins with a firefight of unparalleled violence and brutality. It begins with a narrative poem from war itself feeding on death after Casalanguida and Moore brilliantly depict explosive blood spatter and fiery bullet flashes as incomprehensible numbers of rounds are fired off every second with Hawkins, Kowalksi, and Burke remaining tense but calm as other soldiers around them fill with holes. It is described like nature, like an animal feeding after a flood. War itself does not choose a side. It only wants destruction. War itself does not care about the strength of man, skin or bone. It only cares about the strength of the weapon.

Lost Soldiers #3 is the turn for the miniseries and leans heavily in silence. Other than the poem from war, the bullets and cars provide more than enough force and velocity to drive the momentum forward. The split-second panels where lives are taken or consumed explode in a translucent red, but afterward, even while more violence persists, color begins to fade from the pages. The only color left is the paleness of flesh and the bloods of the body, and most of that fades, too, but the real turn for the book is the death of Kowalski. Not his body, mind you, as Burke leaves him alive for some reason, or perhaps war itself brings Kowalski back from the dead and fills him with rage. After all, war frequently speaks of wielding an army of ghosts, and after his first fight with Burke, Kowalski is a man possessed. We see him still alive as a centipede crawls out of his mouth. This same centipede stains a picturesque fantasy of Kowalski with his wife and kids, a reality that no longer exists. War has crawled within every inch of Kowalski, infecting every aspect of his life.

The latter half of this chapter is a discussion between Kowalski and Hawkins and a bifurcation. For Hawkins, the firefight was a wakeup call. He has a family and wants out. For Kowalski, there’s nothing left but a thirst for revenge. It’s powerful, vulnerable and leans into silence and discomfort. Hawkins confronts Kowalski about his family, and we learn they’re gone. Kowalski says they left, but we find out in issue #5 that he killed them. In the panel in issue #3 where Kowalski explains that his wife left, there’s an overlaid image of what appears to be a woman lying there. It might be clearer in physical copies that she is dead in that moment, but it’s harder to make out in digital. Regardless, Kowalski’s future actions are driven only by revenge. The transformation has occurred, and war is in Kowalski’s body. Kowalski comments on the cycle of pain and deflects any blame from himself.

That deflection is key. It is where the mind separates from reality. For Kowalski, war as a construct shares the entirety of the blame. It was his wife who left. It’s the cycle of war that perpetuates itself and the pain. Kowalski is just a victim. You know how it is.

But that’s not how it is.

Hawkins shows us that. Hawkins gets help. Hawkins cares about others now, and it’s because of that help and that care for others that Hawkins walks away. He takes ownership and leaves as Kowalski continues talking about time, the drums of war and having no real choice but to kill Burke. The most powerful image in this issue occurs when Hawkins tells Kowalski to let it go, and we see a ghostly image of Kowalski, a true depiction of his formless, hollow self, say, “… Let it go when?” As he looks out the window, Kowalski knows a part of him has already died. He’s sad and afraid, but he’s going to get revenge anyways.

‘Punisher’

Lost Soldiers #4 begins with a quote from Yuri Herrera’s Signs Preceding the End of the World. It’s an allegory comparing the American attitude of foreign policy to baseball. This is where war, the construct, the face, the entity that consumes, is shown to have a home. Just as we saw darkness before daylight in Vietnam, the same goes for Juárez. Moore’s bright colors shine here. There are remarkable colorists out there in comics, but Heather Marie Lawrence Moore’s coloring in Lost Soldiers is some of the best in comics ever. It is truly unbelievable the displays of light, shading, saturation, gradient, layering and more effects I don’t even understand that are on display in this series.

In Juárez, just like Vietnam, the atmosphere is tense, but the light of levity peaks through. There is a new narrator now. Kowalski has become a willing vessel for war and is on a mission. Children guarding a safehouse and discussing tacos are mercilessly slaughtered. The brutality on display here is horrifying, and the panel where the bullet penetrates the young child’s neck is one of the most brutal panels I’ve ever witnessed in comics. Kowalski owns what he has become. He almost takes pride in it. He views it as inevitable. He’s bragging about his own atrocities as the world watches aghast. Kowalski has lost all humanity at this point. He’s lost count of the people he’s killed, and he doesn’t feel anything but numb anymore. The past and present become one and the same as the cycle repeats, and Kowalski is stuck looking for a way out. He calls this senseless violence, this war, his therapy. These events are of Kowalski’s own making. It is no longer war devouring, but Kowalski himself. It is one individual who makes the void and one individual who swallows the flesh. When Kowalski accomplishes what he set out to do as the past and present become one, and Burke gives a final word, gloating that it was he who made Kowalski what he is and that Burke will always live inside of Kowalski, another reference to the rape, Kowalski says, “The last emotion I feel is love.” This brings us to the aftermath.

‘Search and rescue’

Lost Soldiers #5 begins with two quotes, just as the first issue did. The first is from Bessel A. van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma and speaks to the possibility of healing after war, of purging it from one’s system, and moving forward. The second comes from Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric with the original context of portraying the exhausting and relentless toll of challenging oppression and channeling the trauma that comes with it, but in the context of Lost Soldiers, it likely applies to the context of how others feel when faced with the American soldier’s perspective of Vietnam. The issue is split between Juárez in 2009 after Kowalski is captured and Houston in 2019 as Hawkins attends group therapy as both of them reach some semblance of catharsis.

On Hawkins’ side, we see there is no undoing. There is no going back. War is not something that can be purged. Trauma is not something that can be erased. There is only moving forward. Hawkins has only now, decades after the idea first occurred in his head, after he realized there is no going back to the person he was before the war. Kowalski never gets the chance to realize that. His thirst for revenge as a tool to get out of the cycle is what digs him deeper into the rut.

Hawkins’ revelation, his monologue in group therapy, is remarkable. It is insightful and powerful and resonant. In many ways, it is the very antithesis of Delroy Lindo’s monologue as Paul in Da 5 Bloods. Paul is alone, delirious and blinded by rage, trauma and oppression. In that monologue, Paul looks at us, the audience and only the audience, and implores us for answers. There is no catharsis, really, only descent. Hawkins finds precisely the opposite. He looks at us, sure, but he also looks at the people who helped him heal and who are all around him. He looks at himself, he looks up and, yes, he looks at us readers, too. But Hawkins isn’t asking for answers. He’s giving them. No, he’s sharing them.

Deep down, I think Hawkins felt many of the same things Paul did. How were they supposed to know going into Vietnam? They had no real name and very little knowledge about the tolls of war, so how were they supposed to deal with it? The odds were stacked against them. It’s a fact. If everyone could learn and if the tools were there for everyone like they were for Hawkins, maybe more could get unstuck. Because Kowalski was never free. Even after he killed Burke, he was still fighting.

He receives another offer to fight for the cartel, to continue the warpath, but he declines. He’s done. Kowalski never escapes, but he’s done. The cartel leader has a great speech about the American story of Vietnam and how it distorts and contorts every way it can so Americans remain blameless. They do this so effectively that for many Americans, it even becomes truth. This speech brought me back to The Things They Carried. A huge theme of that book had to do with the idea of truth vs. reality. Tim O’Brien blended fiction and nonfiction so well that it all felt true, and it was portrayed as a good thing. But despite what feels true, what is real matters. The Things They Carried, as honestly as it portrays some of the horrors of the Vietnam War, carries a torch of romanticism. It largely perpetuates a truth of blamelessness and victimhood. The trauma is real, but the responsibility is hard to find.

Here’s the kicker. Just because the odds were stacked against the men who go into war does not mean they’re freed of responsibility when they come home. War may occur between nations on a battleground with armies of thousands of men on opposing sides, but war also occurs in the mind, and neither construct shoulders all of the responsibility. We’re made aware in issue #1 and #4 about the American military industrial complex and the U.S. as a whole’s responsibility, but even on the individual level within and between soldiers, war alone is not to blame for what goes on inside minds and what’s carried out by bodies. The responsibility must be shared by the individuals who are affected. Hawkins says it himself. He may have seen within soldiers like Kowalski, “eyes that were no longer theirs,” but some of the responsibility has to be theirs as well. That which devours, those that “just get eaten by it, and then they become another … just more teeth, another hungry mouth, and all it wants to do is bite and eat more people alive” is not just an abstract, incorporeal entity. It is a virus. It is a disease. And while it may infect people and cause harm and damage, those people still carry responsibility for the disease’s future trajectory.

We are that which devours. But we can stop. We can satiate the hunger.

In the end, it all goes back to Morrison, I suppose. “Before it was a Bomb, the Bomb was an Idea. Superman, however, was a Faster, Stronger, Better Idea.” Before it is enacted, before soldiers enlist, before they go into battle, before they pull the trigger and before they do it again, war is an idea. John Wayne personifies that idea. Kowalski was John Wayne, but Hawkins became Superman. Hawkins failed to save Kowalski, but others saved him, and he saved others. Grant Morrison believes that once all of humanity believes and embodies the ideas of Superman, that we will all be able to become Superman. The cancer, the part of ourselves in the large organism of humanity holding us back, is John Wayne. Both American icons. Both powerful. Behind one is an army of Superman. Behind the other is an army of ghosts. Fuck John Wayne.

Lost Soldiers will be out in trade Feb. 10 from Image Comics.

Ari Bard is a huge comic fan studying Mechanical Engineering so he can finally figure out how the Batmobile works.