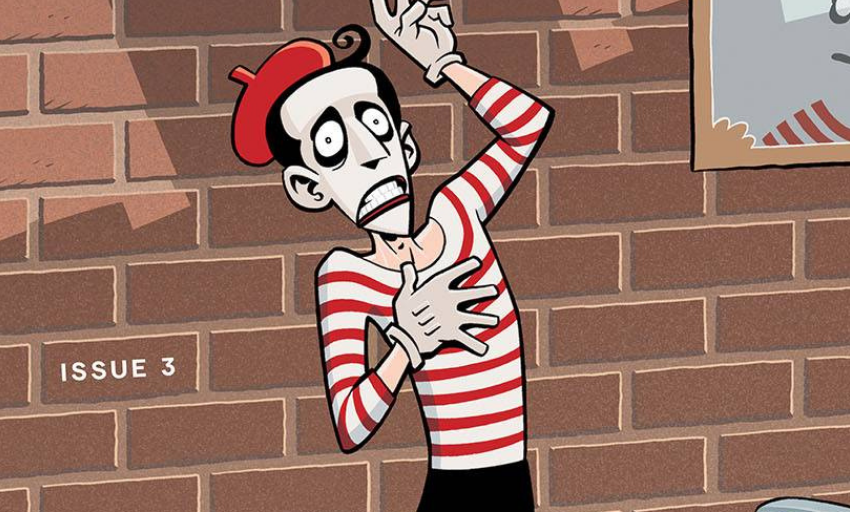

If a mime’s world crumbles into an infinite number of pieces, does it make a sound? Here comes Haha #3, the third issue of our favorite anthology series about the clowning arts. Written by W. Maxwell Prince and drawn and colored by Roger Langridge.

Will Nevin: Ari, what do you think about mimes?

Ari Bard:

WN: I had no idea you felt that way.

It’s the third installment of Haha, the anthology miniseries about clowns and also not about clowns, and this one certainly has its own visual style in addition to Prince attempting (and I’d say pretty well succeeding) in creating an issue without dialogue that’s still able to take up some pretty resonant themes.

AB: Definitely. Prince and his artists are always able to put together a well-crafted story using clowns, a profession on the outskirts of mainstream society, to demonstrate ways in which society may not be all that and champion those who stand up to it. In the case of this particular issue, we can see how powerful even silent actions can be in starting resistance.

WN: On to the show.

It’s All a Cartoon

WN: Let’s take up Langridge’s work first. Not only was it a distinct break from the first two issues (which I suppose is the point of rotating artists), I thought his cartoon style gave #3 a sense of motion and fluidity — things that seem to be pretty important for an issue featuring a mime. How did this work for you, and did this remind you (like me) to finally read Criminy?

AB: I loved the art in this issue, and Criminy is definitely on the long list of things I need to read but has definitely moved toward the top after this issue. Langridge and Prince execute such a delicate balance in tone here between a very light, almost Disney-like cartoon style with a very pointed and determined message. In many ways, it’s a 30-page political cartoon. There is such an intelligent use of page management going on in this issue. Remi constantly pushes against panel gutters functioning as his invisible box. Floors, walls, screens and frames are used as gutters, and it’s really neat to see.

WN: I hadn’t even picked up on that use of the gutters — excellent eye there, my man. I think it’s right to frame this as a Disney look, especially when you factor in the bright coloring. Do you think that style — juxtaposed against the despair at the root of the story — serves to heighten the inherent sadness, blunts it or some mix of both? Or neither, I suppose.

AB: I think it serves to display the inherent clashing of two very different perspectives. I think we’re constantly getting bombarded with messaging that everything’s fine and we’re all going to be OK, but we can see on a very personal level that’s not the case. The bright and shiny look is just the messaging on the surface and the facade that we see all around us, while the despair at the root of the story is what individuals are actually feeling.

The Sound of Silence

WN: If you’re going to feature a mime in your comic book, you’re probably not going to have too much talking. And if you’re gonna do that, midas whale go for the thing and cut out all of the dialogue. To me, this read well and was a great execution of the gimmick — I liked this quite a bit more than I cared for Ice Cream Man #23, which was Prince going the opposite way and giving us a mostly prose piece.

AB: Yeah, I don’t think the two issues can really be compared, but I do really appreciate the choice to do this as a mostly silent issue. I think a lot of silent comic issues are done for pure gravitas or impact, but this was done to comment on the silence itself. We’re able to see how noisy the world can still be even when nobody is speaking, and we’re able to see how powerful actions without words can be and how gestures can inspire change.

WN: Ari, I’m a simple man: I like my steak rare, my bourbon neat and my coffee black. And when I see a comic with all of the words and a comic with none of the words, and they’re by the same fella, I’m gonna compare ’em. You are right, though: The storytelling here is solid.

AB: Definitely, and speaking of storytelling, let’s jump into what actually happens in this one.

The Day the Clown Cried

WN: Our story here is pretty straightforward: Remi (a mime) is having a rough time with his act (I thought for a second there, by the way, that we were going to rehash #1) until he finds Marcel, a robot that can effectively mimic his mimery — until Marcel is taken away, leaving Remi to quest for the return of a tool that has become a friend and maybe something more. There’s some real emotion here, a profound sort of sadness — almost like what we got in Hollow Heart. Even if you take away the animated style and the silent gimmick, there’s still a lot that powers this issue.

AB: I think I’m able to grasp a lot of what Prince is trying to go for with this issue, and with Haha as a whole, through the reference besides clowns he alludes to once again in this issue. Through the imagery of the little girl’s frog in a cardboard box and J.C. Wilber once again having his hands all over the story, my mind can’t help but go back to One Froggy Evening, and I think that’s where Prince’s mind lives with this series as well. It is a masterpiece of animation with every member of the animation team working synchronously at the peak of their craft to create something around seven minutes long that is still able to say so much, and that’s very similar to what Prince is trying to achieve. One Froggy Evening speaks a lot about the general futility of it all, mostly in relation to greed, but Haha shows us a group of individuals whose very existence is something many of us many consider futile. Don’t get me wrong, obviously everyone’s life has purpose, but there are many who just do not see meaning in the professions of people like clowns or mimes. Haha shows them and how they push through futility, whether it be through rejection, acceptance or resistance.

WN: Issue #2’s J.C. Wilber Short Stay hotel makes a lot more sense now, and I feel like a complete dipshit for arguing they couldn’t have been making a One Froggy Evening reference. Did Prince plot out #3 and work backward to include that nod in #2? I guess that’s a rhetorical question unless you have some inside information. Who is the little girl to you, and what did that ending say to the theme of resistance?

AB: While it’s certainly possible he worked backward, I could also see a case where he may just be inspired by the short information enough to where it’s become a theme of this series. I think the little girl is meant to be those who carry on the torch of resistance even amid defeat or a setback. It also demonstrates how contagious actions, especially actions of resistance, can be in a good way. I think it’s great that the little girl finds inspiration in someone and something as eclectic as Remi and his bond with Marcel. Hopeful she carries on the resistance.

WN: Marcel’s creator (Wilber, I presume) discards him only to later demand his return. He gets him back and then seems to scrap him. What do those character choices say to you?

AB: I think Prince is commenting on how society and employers largely value people for as long as they prove to be useful to them. Marcel was labeled as possibly defective. For whatever reason, Marcel functioned in a way that may be considered different or less useful to others. Marcel’s creator and guardian discards him and devalues him because of this. Then when Marcel proves what he can do and demonstrates value, Wilber demands him back, not as a being of value, but as something to examine and exploit. “How can we best extract value?” That is the question being asked here with no regard to Marcel’s wellbeing. Marcel can represent many different types of people in our communities that we largely disregard until we see why they are needed, and oftentimes, when other disregarded individuals like Remi try to save them, all we see is more bloodshed and judgement. What did you think?

WN: You may have primed me with “employers” and “exploiting,” but this really makes me think of how labor is often abused by the monied classes. Marcel was worthless until he demonstrated value, then he was simply another thing to be broken and once again thrown away. That relationship is a stark contrast to the one he has with Remi, an understanding that seems to be built on respect and what I read to be love.

Finally, one more point: What did you make of Remi’s practice of turning on television news and then hitting the mute button?

AB: I don’t think we see quite enough to make a definitive conclusion, but if I had to speculate, Remi is tired of hearing pundits and news anchors spinning something objectively bad into something good using words. What’s documented on camera and displayed on the screen isn’t unbiased, but perhaps it is less biased, and Remi is best able to absorb information and assign meaning that way. That’s just one theory, however. What did you think about that scene?

WN: I thought about those moments a lot because they were ones I didn’t instantly decode as I was reading the book. Reflecting on them, they seem to be an extension of Remi’s mime work: When he performs for the public, he provides movement and audiences import meaning. Without sound for TV news, he can assign the meaning as he so chooses — in a way, rejecting the reality around him like a certain clown from a few issues ago.

AB:

WN: Absolutely.

Here’s the Punchline

- Marcel (the robot who makes “bip” noises) is a reference to history’s most famous mime, French actor Marcel Marceau and his character “Bip the Clown.”

- Clown trivia: The first clown characters were created in Egypt and date to 2,400 BCE.