“Why am I like this?”

What a loaded question right? It definitely comes with a burden of uncomfortable introspection and contemplation about the changes we might want to make moving forward. After all, we can’t change the past, right? What we’ve already done, for better or worse, is permanently imprinted onto us, and what people choose to do with that is outside of our control. The external and internal ramifications are two very different things.

Sean Lewis, Caitlin Yarsky, and Ari Pluchinsky attempt to explore this question from a primarily external perspective in their series Bliss by diving head first into a sea of inquiry about how we come to be who we are and whether it all matters, quite literally. The first page features Benton Ohara, a man who has done terrible things and our protagonist Perry’s father, diving off of a cliff into the lake below as Perry takes comfort in the inconsequentiality associated with knowing he’s just a blip in a vast universe. It’s a page bathed in a deep purple hue that invites you to linger and get lost in its questions. Frankly, that’s the strength of Bliss as a whole. It doesn’t know the answer.

Bliss is a raw, melting pot of emotions that, oddly enough, provide a comforting messiness to a complicated story. Feral City is a fictional urban center that lies in the middle of nowhere. Think of any city in America with desert and farmland for miles once you get outside of the city center. It’s not big enough to gain any outside attention, it’s too isolated to escape from, the only people coming in and out often have an insidious agenda, and it’s too big to be effectively managed by a municipal government alone but too far away and unproductive for a state government to get involved too option. Somewhere has to pop into your head after all that? It’s a place so clearly rendered but never explicitly stated, and the demeanor of Feral City’s people is even clearer: they’re trying to survive, they’ve been hurt, and they’re angry. Rightfully so.

Toxic capitalism and rampant neglect have left people without answers. It’s been this way for a while. That’s why many years ago, Benton made a choice to save his son stuck in the hospital with an expensive medical condition by becoming a hitman for a supernatural cartel… and using the drug Bliss, which comes from the river on the edge of the city, to forget all of his cruel actions. But the people still remember, and now it’s up to Perry to defend his father before the goddess of oblivion destroys them all. It’s a big premise, isn’t it?

A community who has only known an individual for the crimes they’ve committed against an individual who has also seen their love and selflessness. What do you do? What do you do when someone you love has done a terrible thing? The easiest answer is to forget. For a while, that’s the path Bliss travels down. More than just the “forgive and forget” cliche, Bliss forces people to forget because they may not be able to forgive. Otherwise the pain would paralyze them.

I’m not sure I’ve ever felt pain in that way before. Most of the time, pain tends to have more of a dissociating or numbing effect. I just start to carry on with the day-to-day routine while slowly feeling less about everything around me. I try my best to remain cognizant of this, because without anchors to pull me back, I’m unsure how far into a state of unfeeling I’d go. The one or two times I have felt intensely hurt in a paralyzing way, I forced it out of me. I forced the state of unfeeling because I couldn’t fathom the idea of dropping responsibilities in a world constantly moving forward just to feel. It was a completely foreign concept to me and probably had some long-term detriments.

That’s why, despite being a messier comic overall, Man-Bat from Dave Wielgosz, Sumit Kumar, Romulo Fajardo Jr., and Tom Napolitano also tends to hit pretty hard. It’s a Big Two miniseries featuring a Batman character, so it’s tied to a Gotham City plot that doesn’t do it any favors. At its core, however, it’s a story about a man who, despite his intentions, has always messed things up for himself and Francine, the woman he loves. Some of it is the result of circumstances and accidents that aren’t his fault, but most of it is because of circumstances Kirk Langstrom keeps putting himself in, whether he decides to take accountability or not. Man-Bat is about a man so afraid to confront his own actions that he creates a literal monster inside of him to project his evils onto. Perhaps it was Dr. Jekyll that was evil all along.

Perhaps if Kirk Langstrom had Bliss, Man-Bat would just fade away instead of all the hate manifesting as a monster. Probably not though. The thing about Bliss is that it makes your mind forget, but everything you do stays imprinted on your soul, and Benton’s took a beating. Mabel, Benton’s wife, and Perry were going to notice sooner or later. Loved one’s always do. It’s up to us to listen to their concerns. Benton didn’t listen to Mabel or Perry. Kirk didn’t listen to Francine or Batman. I try to listen. I really do.

Memories, deeds, don’t just evaporate. They have to go somewhere. In Bliss, they go to the river where Lethe, the goddess of oblivion lives, and as the river rises and overflows, Lethe plans to travel it to Feral City and destroy it. In Man-Bat, the memories simply travel from Kirk to his other persona, the monster inside of him. Once created, they can’t be destroyed. They have to go somewhere.

Where does my pain go? Sometimes I feel like it was never there. Not like it should have been.

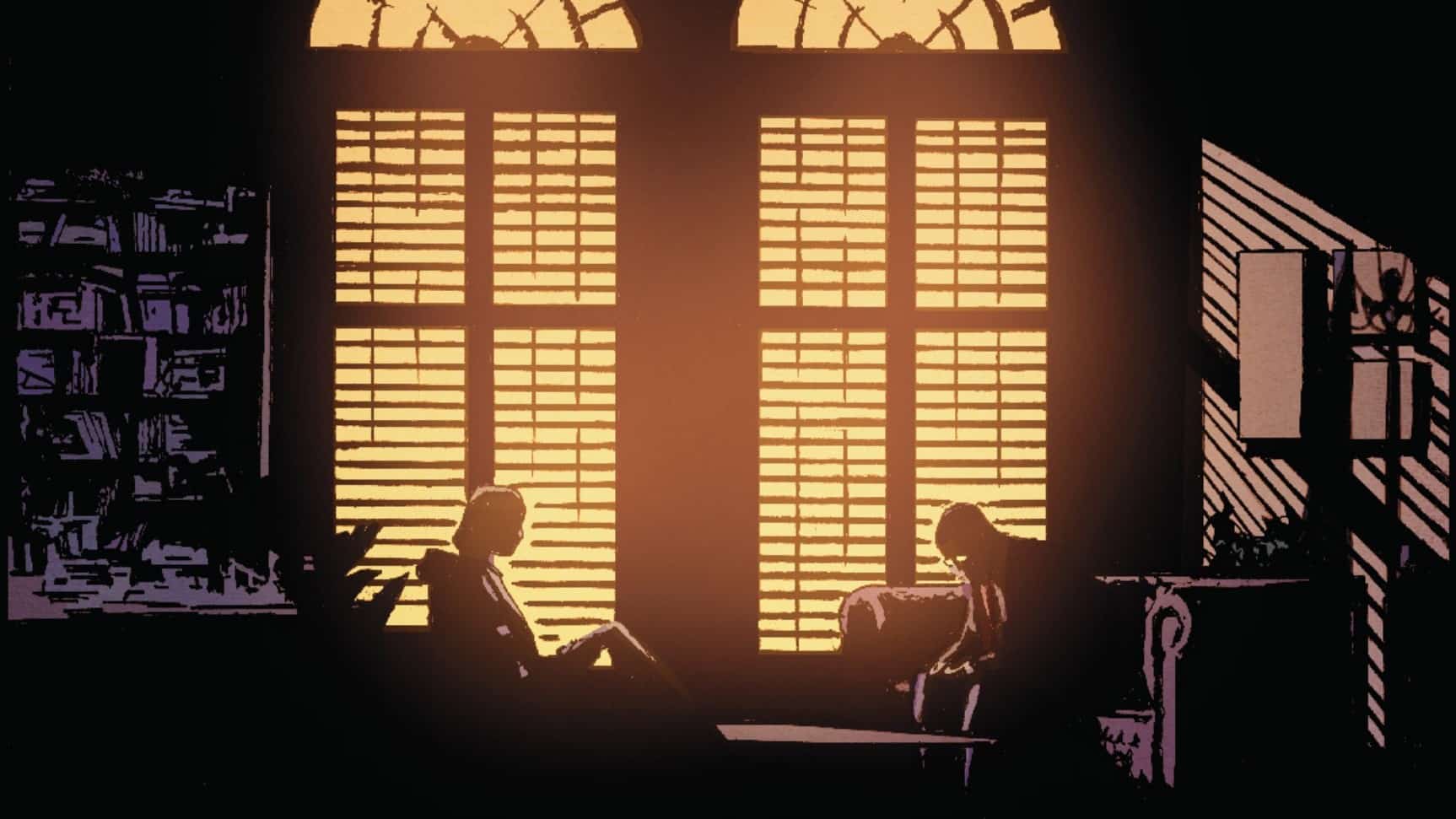

Both Bliss and Man-Bat are told with an essential degree of uncertainty, as it’s impossible to completely grasp the conflicting forces of love and judgement at play here with an absolute answer. Instead, both comics grasp these forces through unique layouts and styles. Bliss is highly expressionistic and, for lack of a better word, round. We’re so used to modern, sleek comics with sharp, angled lines and formal, structuralist grids. Caitlin Yarksy’s style is one of the most memorable I’ve ever seen because she seems to throw all of that out the window. Her style is asymmetrical and winding, intensely evoking the art nouveau movement and early 20th century architecture. That’s where the judgement comes from. Buildings are often massive and reminiscent of large cathedrals, filled with space and yet crowded with judgement. Most panels never show the complete scene or action, rather giving the readers only a partial glimpse. Yarsky consistently references imagery of divination such that the readers feel they can see what’s going on, but never with conviction. The love comes through in the expressions and gestures. Reminiscent of renaissance portraits in their detail, Benton’s shame and guilt, for example, radiate off the page. The sliminess of Bliss oozes from each panel and from many word balloons as characters take the drug.

Man-Bat approaches things a bit differently. Love is primarily conveyed through words, often monologues from Kirk or Francine juxtaposed between constricting scenes filled with Scarecrow’s fear toxin. Judgement is often conveyed through perspective and power. Violent action sequences where heroes and villains alike only become bigger and more menacing. Kumar’s art consistently employs towering perspectives where we are looking up at a figure looming over us or down and a character who is struggling.

Both love and judgement are essential in these stories. Without love, there’d be no empathy; no understanding. We’d simply see these characters as bad people and say, “Serves them right,” as they receive their consequences. Without judgement, we’d simply forgive them while ignoring their negative actions. It’s pretty hard to stick with someone and reckon with what they did. I’m not sure I’ve come across that situation yet. I’m not sure what I’d do.

Eventually, Benton travels so far down the rabbit hole that he’s assigned the task of killing his wife or losing his son. An impossible choice, but one he makes with the help of Bliss. I would not say that Bliss is necessarily a story about addiction. I’m not even sure Benton’s dependence on this drug is an addiction as much as his need to forget. Are they effectively the same thing? I’m not sure. Is Kirk addicted to his serum or does he simply need to lose himself in something else in order to feel like he can get the job done, like he can be enough? Maybe those are also effectively the same thing. I’m not sure about that either.

The back half of Bliss gets a bit messy. In the past, Mabel and Perry snap Benton out of it, get him off Bliss and force him to remember, after which he goes away for a while. In the present, Lethe sends her crows after Perry and Benton while Benton sets out to confront Lethe on his own. The problem is Lethe is too abstract to be imposing. She’s a towering, immortal goddess, sure, but there’s a lack of foundation that gives her any substance, especially when the strength of the flashbacks is enough to keep the pages turning. The giant skeleton crows and supernatural elements are impressive, but at this point in the story, it’s the recurring check-ins with Perry and how he sees his father, lines like, “What he did kills me. But I can’t help seeing him as a dad. My dad,” that keeps me reading.

I think we all have an oblivion we have to confront ahead of us, but that’s going to be something different for each individual. How we see our flawed loved ones, how they can kill us and yet we can’t stay away, maybe that’s a little more recognizable. Man-Bat has a similar issue. The confrontation between Scarecrow, Man-Bat, and Batman isn’t all that exciting. In fact, it really drags the story down.

Man-Bat’s saving grace is Kirk’s final conversations with Man-Bat and Francine. In the first, he’s forced to reckon with the fact that Man-Bat and Kirk are the same individual. The anger, mistakes, and negativity he always projects onto Man-Bat has always been a part of him, and Kirk needs to confront that to move forward. In the latter, Kirk has to accept that there are some things he can’t fix, including his relationship with Francine. “I want you to be happy. I want to be happy too. But after all I’ve done, I understand we can’t be happy together.”

God that hurts. It takes me a long time to form any sort of connection to people. Most don’t have the patience for it, and I don’t blame them. Once I form them, however, they grow and harden quickly. The thought of severing them completely, no matter where our lives lead us, is really hard to bear because it’s hard to say when or if I’ll ever form another connection again. My inclination is always to bend and make it work no matter how far apart we stray, which… isn’t the healthiest. It wouldn’t be right for me to force people to wait for me to grow or deal with some shit. I know that. It isn’t great for me to put parts of my life on pause for others either. I know that too and yet, the temptation to throw everything to the side for the chance of two pather reconverging is always there.

Benton was sick, and when he went away, he did the right thing. He went to rehab. The Memory Palace, a treatment center for Bliss. It was hard. Benton tried to give up a lot. First when the memories wouldn’t come back, then when they started to. It was easy to think that apologies, confrontation, or material gifts might make things right when you’ve deeply hurt someone. They don’t. Some kinds of pain are irreversible. The true path to forgiveness is much harder. Benton had to remember everyone he’d harmed, and the only person that kept him on a healing path was Perry.

I’m not sure I have a person like that. I hope I do. I hope I’m that person for someone, but you never know do you? Not until something happens.

There’s a generational component to Bliss that doesn’t resonate to me as much. The intense love and conflict between father and son isn’t as present in my own life, but you can’t help but feel its power when reading Bliss. The idea that the answer to, “Why am I like this” can simply be found in one’s parents is always there, and you can’t blame Perry for thinking there are pieces of Benton inside of him. Pieces of our parents are inside all of us, whether we like it or not. Sean Lewis writes an extremely heartfelt coda about his experiences with his own father that reveal just how deeply personal this story was and just how strongly this creative team believes in their message of change and breaking generational cycles of bad behavior. It’s a powerful testament to the idea that change is possible if we commit to putting in the work and doing it the right way. I may not have had a reckoning with my own parents, but it’s certainly a message I can get behind.

Benton’s reckoning doesn’t come with Lethe or Perry, rather with the people of Feral City. Lewis, Yarsky and Pluchinsky wrap up one hell of a story with a powerful collision between those Benton’s harmed and those he has helped while on his quest for rehabilitation. Those from the Memory Palace see the good he’s done and don’t want others to be trapped in their own shame and anger, and so we hear testimonial after testimonial from those Benton has helped and hurt, about those Benton has killed and saved. Imagine all of your actions that deeply affected people, good and bad, are presented before you. How would you feel? How many would there be?

Imagine you were hearing all of those things for the first time. Could you live with yourself? Benton is encouraged and chooses to let the river decide his fate. Same as the story began, Benton dives off the cliff and into the river, which now makes people remember instead of forget. Whether or not he survives is up to nature and Benton himself.

The question, “Why am I like this?” is never answered. I’m not sure Perry cares when everything is said and done. Instead he pursues a different line of questioning.

“What is forgiveness? Is it absolution? Or is it something we shouldn’t have at all?”

I think both lines of questioning might be related. Maybe forgiveness is learning to reckon with the uncertainty of why we’re like this. Perhaps understanding how people’s experiences have shaped who they are, and in turn who we are, is what allows us to forgive them. Maybe facing why we are the way we are ourselves is what will allow us to receive forgiveness from others.

I’ve looked a lot at my past. I’ve written a lot about the monster I might have become and person and am instead. I certainly haven’t always been the most empathetic person so far in my life, but I’m working on it. I’m certainly quick to forgive and seek understanding after reckoning with who I might have become. I hope I’ve done enough to be responsible, maybe even to earn forgiveness. But that’s not up to me, and it never will be.

Ari Bard is a huge comic fan studying Mechanical Engineering so he can finally figure out how the Batmobile works.