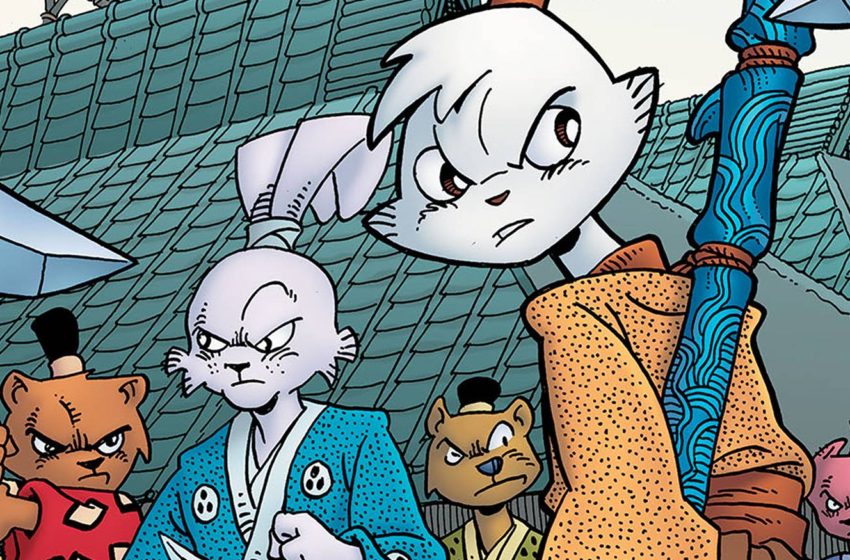

Usagi and Yukichi have left Lord Hikiji’s province, so their troubles are behind them … or so they thought! They meet up with Kitsune, the street performer/thief, who brings her own troubles. Kitsune has stolen a ledger recording bribes by a gang leader to local politicians. Usagi wants to turn it over to the area magistrate, but she wants to sell it back to the mob leader. What’s a samurai bunny to do in IDW’s Usagi Yojimbo #22, written and drawn by Stan Sakai, and colored by Hi-Fi Design.

Stan Sakai introduced the character of Kitsune during the first volume of Usagi Yojimbo (#32, Fantagraphics, 1992). With her spark of chemistry with Usagi and her playful irreverence, she quickly became one of the comic’s most prominent and beloved recurring characters. A street performer and thief, she lives by the mantra “A girl has to do what she can to get by.”

From the start, she’s been portrayed as an equal to Usagi, not as a fighter (though she has some skill in that area), but as a survivor. While Usagi tries to live according to the law and his own personal sense of honor and justice, Kitsune does not have the luxury of being born into a noble family and trained as a samurai. And so when Usagi takes to the wanderer’s road, it’s with a certain amount of respect. He may be a wandering, homeless bodyguard, but he’s noble.

We’ve seen a lot of Usagi’s childhood. He was the son of a local magistrate. He had friends, a loving family, studied under the best sword trainer in Japan and rose to the rank of general before having to live the life of a wandering ronin. Not so with Kitsune, for whom such a life was never a possibility. The daughter of an unsuccessful merchant, she was sold as a servant to a local inn, then sold to a brothel before running away and turning to petty thievery to survive a life on the streets. She was then taken in by a street performer, Sachiko, who trained her in the ways of performance and thievery. Many years later, she in turn recruited another street urchin, Kiyoko, to become her own protégé.

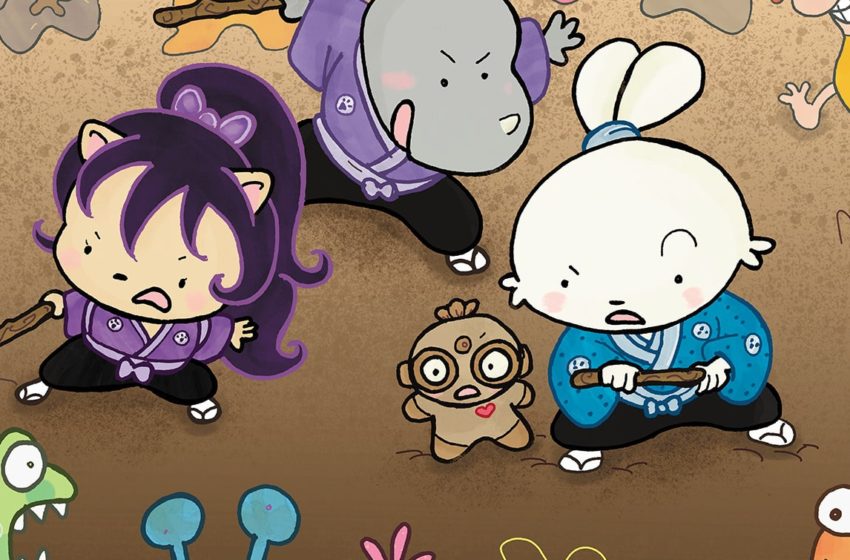

And so now, in issue #22 of this latest volume, we see Usagi’s story parallel Kitsune’s in a new way: Usagi has taken on a protégé of his own, his cousin Yukichi, who now finds himself a wandering ronin like his older cousin. Yukichi’s first encounter with Kitsune and Kiyoko echoes Usagi’s first encounter with Kitsune, with Kitsune stealing Yukichi’s purse and Kiyoko somehow managing to steal his swords. Sakai handles the scene with more flair this time, though. In the 1992 story, Kitsune’s pickpocketing happened between panels. Here, if you pay close enough attention, you can see where Kitsune obscures the act from the reader; a nice trick in itself. With each act of legerdemain, the reader is tempted to read back what they’ve just read, in order to see where Sakai executed the trick, to look at where both of Kitsune’s hands are, to notice when things go missing from the panel.

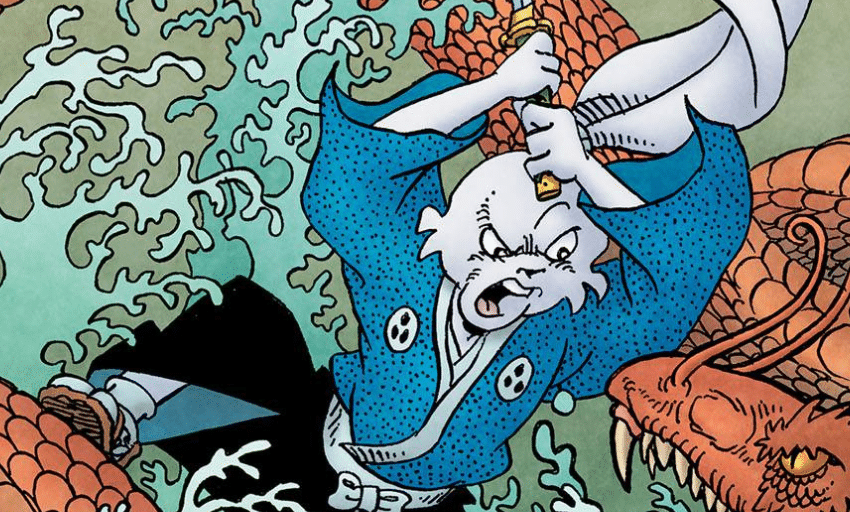

While this scene is played for comedy early on, Sakai uses a similar execution late in the issue, when Kitsune tries to escape an ambush with Kiyoko. He uses the action of the frenetic chase through narrow alleyways, focusing tightly on Kitsune’s terrified running, showing panel after panel with no dialogue that would only slow the reader’s attention. On the final panel of the page, he reveals that Kiyoko is missing, and has been for two-thirds of a page.

It’s a shame that IDW chose to spoil the ending of the issue in their solicitation, which somewhat lessens the impact of this climactic reveal. Still, it’s a treat to read, if only to see how Sakai’s craft has evolved and sharpened in the last 30 years of telling Kitsune stories.