November 11th was the birthday of longtime X-Men artist Dave Cockrum, who passed away in 2006. In his honor, it’s also the unofficial birthday of his favorite mutant, Nightcrawler.

I like Nightcrawler quite a bit. But I’m pretty sure Cockrum loved him more. Cockrum created a version of the character years before he became a professional comic book artist, then refined him for a Legion of Superheroes-related pitch before finally finding him a home among the X-Men, beginning in Giant-Size X-Men #1. Over the years, Cockrum came to closely identify with the X-Men’s resident blue-furred, forked-tailed teleporter with a heart of gold, something he discussed often in interviews and interactions with fans. Chris Claremont contributed crucial characterization, and other writers and artists have taken Kurt Wagner in different directions. But when people talk about “fun” Nightcrawler, the sexy swashbuckler wielding cutlasses in his hands and tail while beaming a devilish grin, they are, whether they know it or not, talking about Cockrum’s Nightcrawler.

To celebrate Cockrum and Kurt’s shared birthday, I like to revisit a favorite moment from their time together. This year, I’m revisiting the four-page opening sequence from Claremont and Cockrum’s Uncanny X-Men #147, originally published in 1981.

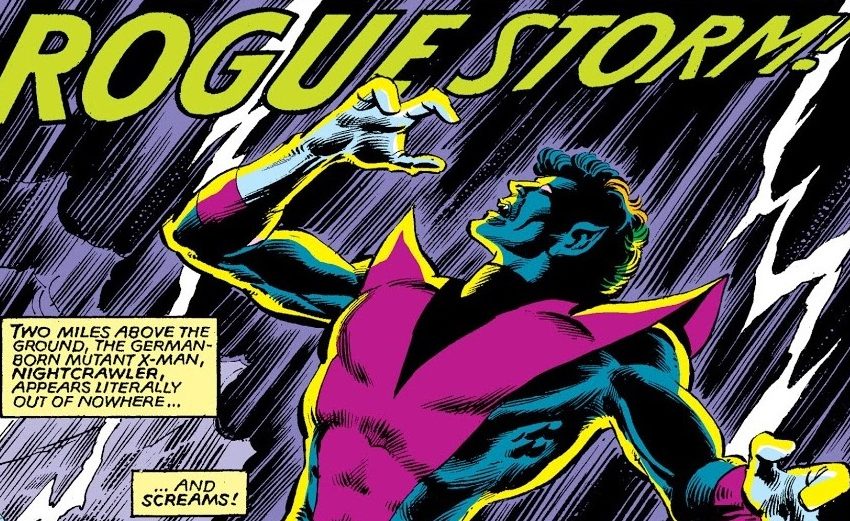

Kurt doesn’t get the cover of Uncanny #147, but he does get the opening splash page. And what a splash page it is. The first time I encountered this page, Nightcrawler was already my favorite. I didn’t need to wonder about the identity of this disco demon majestically yet painfully pinned against a purple sky torn asunder by wind, rain, and jagged lightning, a gothic castle crouched amid the mountains miles below his two-toed feet. Nor did I have to wonder how he got there. In the previous issue, Kurt was imprisoned by Dr. Doom inside a featureless box, a supposedly perfect trap, since Kurt needs a line of sight to teleport; “blind” teleports risk many grisly deaths, including materializing inside objects or people. But, for the sake of his teammates, Kurt did it anyway, teleporting blind two miles into the sky above Doom’s castle. Yet knowing Kurt and the context didn’t dampen the thrill of this splash page. Cockrum still manages to make our mutual fav feel surprising, strange, and amazing.

Comics scholar Scott Bukatman argues that superhero comics offer “a corporeal, rather than a cognitive, mapping of the subject into a cultural system.” In other words, superhero comics can be read as a “body genre,” their symbolic and cultural meanings written into and expressed through the fantastic bodies that animate their plots and defining spectacles. Essentially, superbodies look like what they can do and what they are. That’s their iconic power; the purest superhero designs communicate, at a glance, a character’s relationship to the world. Sometimes, this is done through resonant colors and symbols and hard muscles expressing indomitable spirits. Other times, it’s done by reshaping fictional flesh—into air, fire, water, rock, or whatever Nightcrawler’s supposed to be.

So—what is Nightcrawler supposed to be? The equally easy and complicated answer to that question is that he’s many possible things, in different moments and all-at-once. And it’s all here in this splash page. Some of Kurt’s features—his forked tail, his two-toed hands and feet, his pointed ears, his blue coloring, his fangs, and his glowing yellow eyes—clearly resonate with classic images of demons, especially though not exclusively those appearing in Western art. But because Kurt’s most often smiling, kind, and unimpeachably good, he’s usually, as Kitty Pryde calls him, more of a “fuzzy elf.” Here, though, the gothic cues and Kurt’s estranging silence—the captions tell us he screams, but the sound is visually absent—play up his demonic-ness. Consequently, the opening splash of Uncanny #147 offers a thrilling reminder of Nightcrawler’s un-domesticatable difference.

Yet if you’re at all familiar with superhero comics, you’ll also see this page and know, instinctively, that Nightcrawler’s a hero. Those well-defined, perfectly proportioned muscles are typically the purview of goodguys, and the sympathy etched into Kurt’s pose definitely is. Villains wilt, crumble, combust, and contort under pressure. Heroes do what Nightcrawler’s doing—they suffer beautifully, because their suffering is our suffering. But Kurt’s heroicness never eclipses his monstrousness. He’s both a hero and a monster and many more things besides, his spectacular physical contradictions colliding and multiplying in the eye of the beholder as he struggles, in this monumental splash page, to hold himself together. That’s why I love this page—because it perfectly captures Nightcrawler’s radical multiplicity.

The context of this page—the fact this dramatic moment is the result of a risky blind teleport—also matters a great deal, both to me and to the deeper meaning of this page and the scene that follows. Superbodies are super in part because they’re super-meaningful. And they’re super-meaningful in part because they’re super-powerful. But power doesn’t simply mean strength. Despite their insistence on solving most fights with punches, superhero comics offer fascinating meditations on the varied meanings of power, enacted through experiments with different types of (super)powers. Nightcrawler has enhanced agility and the ability to stick to walls, but his most memorable superpower is teleporting; he can, with a thought and some vaguely defined physical effort, disappear from one place and reappear almost instantly in another. For a character actively persecuted for his appearance, who joined the X-Men because a torch-wielding mob was about to drive a stake through his heart, this powerset is deeply resonant. As compensation for his particularly intense persecution, Kurt is granted the power to escape.

But it’s a power with important costs and limits, as documented on page two of Uncanny #147, courtesy of Claremont’s customarily wordy caption boxes and thought bubbles. We’re told the range of Kurt’s teleportation depends on his strength and stamina, as well as the direction he’s trying to go; north-south ‘ports “along the Earth’s magnetic lines” are easier than east-west ones, and vertical ‘ports are “the most difficult, and dangerous.” That’s why Kurt screams when he materializes in the sky, and why he “greyed out from the strain” of his heroic act.

You could argue the cavalcade of captions and thought bubbles makes this a poorly designed page. Most 21st century comics would do less telling and more showing, relying on expression and composition to communicate Kurt’s physical peril and internal turmoil. And overwhelming dynamic action with text can be the mark of a writer who doesn’t trust the artist. But in this instance, I think Claremont and Cockrum are on the same page. And that page is this page, which wants readers to be very sure of a few very important things. Claremont and Cockrum want everyone to know precisely how Nightcrawler’s powers work because they want to be absolutely sure everyone knows, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that Nightcrawler is really fucking great.

Kurt’s great because he’s heroic, in a reckless, passionate, selfless way that makes me weak in the knees. And it’s all informed by his particular brand of teleporting. In the opening sequence of Uncanny #147, the textual and visual evidence of Kurt being nearly ripped apart reminds us that teleporting threatens integrity; bodies that disappear may not reappear whole. In effect, each of Kurt’s teleports is both a leap of faith and a sacrifice, always painful and unpredictable (not to mention noisy and smelly). The fact Kurt continues to teleport anyway either/both informs or extends from his defining optimism. His powers require and bolster faith, perhaps in a religious sense, though not necessarily. Notably, Nightcrawler wasn’t canonically Catholic when Uncanny #147 was published, and Cockrum was strongly opposed to this development, which happened in the Claremont-penned, Paul Smith-penciled Uncanny X-Men #165 (1983), the first issue after Cockrum permanently departed as the book’s regular penciler. As such, while Kurt’s faith can be an extension of his Catholicism, it’s not reducible to that. He has faith in goodness and fairness—both local and metaphysical—because he has to. If he didn’t, he couldn’t enjoy his mutant gifts. Assuming you don’t have a death wish—to be willing to disappear, you need to have faith you’ll reappear.

But while I do think Claremont’s words add important context to Cockrum’s art, it’s the art that truly sells me on the concepts and conflicts at play. On page two of Uncanny #147, each panel matters. In the first long panel, Kurt falls limply, a helpless victim of gravity. His tiny body is placed at the bottom of the panel, overwhelmed by wind and rain; even the caption boxes bear down on him as they drag our eyes across the page, following the zig-zag path of the lightning and the implied path of Kurt’s fall. In the next panel, we shoot back to the top of the page, where we see Kurt starting to right himself. His muscles are shaded darkly to show them tightening as he begins bending upwards, against the force of gravity and the weight of the rain. To emphasize his renewed power, his body is large and centered in the frame.

The next panel, featuring a closeup on Kurt’s face, aligns us with his perspective. We don’t see through his eyes, but we do see what he’s seeing by seeing the determination on his face as he sees it. In the following panel, Kurt soars, resembling the trapeze artist he used to be. And in the final panel of the page, the rippling muscles in his back (and, yes, his glutes) show him fully regaining control. He starts falling with determination, aiming himself at a target. Throughout the sequence, Cockrum makes great use of Kurt’s tail to both reflect his emotional states and illustrate motion. When Kurt’s body is limp, his tail is equally so. In the panel where Kurt rights himself, his tail curves into a firmer scythe shape, forked tip pointing decisely upwards. It’s a calm s-shape when he’s soaring and shoots straight up when he’s determinedly falling. Functioning similarly to a cape, Kurt’s tail adds dramatic flourish to his movement through the sky.

But Kurt’s determined fall is merely the eye of the storm. On the first panel of page three, Kurt swoops up on a wind current, then teleports. The “BAMF” sound effect panel generates tension and offers another potent reminder that teleporting is both wondrous and dangerous, liberating and disorienting. When Kurt reappears in the next panel, he hovers for a moment in an action pose above the water before a final, painful submission to gravity. That’s another drawback of teleporting; Kurt materializes at whatever speed he was moving when he ‘ported. The visceral speed and force of Kurt’s final fall is generated, in part, through juxtaposition—by the whiplash of jumping from Kurt’s powerful body defying gravity above the water to him becoming a tiny shape beneath it. Though the panel depicting the water plunge isn’t elongated, the change in perspective makes it read as if it is. This seeming elongation, combined with the fact the massive backsplash on the surface of the water is still shooting into the air when Kurt’s already thirty feet below the waves, further emphasizes the force of his fall.

Claremont and Cockrum could cut straight from here to the shore, either by having Kurt teleport or simply telling us, in a caption, that he swam. Instead, they decide Kurt’s too weak to teleport, and proceed to milk the pathos. This may be my favorite bit of the sequence, in no small part because of how Cockrum humanizes Kurt. Some artists treat Nightcrawler’s monstrous features as an invitation to cartoonishness. John Byrne was sometimes guilty of this; amid worlds otherwise beholden to smoothly rounded realism, Byrne typically minimizes Kurt’s facial features and occasionally gives him comedy bugeyes. But in Uncanny #147, as Kurt fights his way to the surface and then to the shore, Cockrum employs naturalistic facial expressions and postures. He also carefully renders Kurt’s hair, showing his curls loosening and straightening in the water. This might seem like a small thing, but small things are sometimes big things. By giving Kurt’s hair texture as well as shape, Cockrum makes him more touchable. Which makes him more real, which makes him more identifiable, which makes him more heroic. Kurt’s sudden, too-human vulnerability is both a shock and an irresistible invitation to root for him.

But even though Cockrum’s pencils carry the sequence, I still wouldn’t dream of criticizing Claremont’s copious thought bubbles. Because if we didn’t have the thought bubbles, we’d never learn about Kurt’s fear of his own fangs, which threaten to “cut [his] lips and tongue to ribbons” if he can’t stop his teeth from chattering. This raises a lot of questions. If Nightcrawler’s fangs are that sharp, would that make it difficult to eat? (What about kissing??) But I’ll allow it, because it allows Claremont and Cockrum one more opportunity to hammer home the complicated symbolism of Kurt’s mutant body, which lets him survive an ordeal that would assuredly kill any regular human, yet constantly threatens to betray him, in ways both spectacular and minute.

Page four effectively concludes the sequence. This page spotlights Kurt’s face, water-logged curls still dripping down his dramatic cheekbones and off his firmly set jaw. His disembodied head is the centerpoint of six flashback panels separated by lightning-inspired gutters. Caption boxes recap how we got here, but it’s Kurt doing the remembering—the flashbacks extend, literally, from Kurt’s mind. I find this page nearly as thrilling as the opening splash, for one simple, very subjective reason—because it presents Kurt as a point-of-view character, not just for this scene or this issue, but for the story arc as a whole. He’s not a mere participant in the story; he’s positioned at the heart of it.

It’s silly to complain about X-Men comics not having enough Nightcrawler. He is, objectively, one of the franchise’s most prominent characters. But outside of Excalibur and his own short-lived solo series, Nightcrawler was and remains a rare point-of-view character. That’s evident in the flashback panels on page four of Uncanny #147; Kurt’s only featured in two scenes, and in the group shot, he’s at the very back, crouching on a table to peer over the shoulders of Colossus and Wolverine. Kurt’s my point-of-view character regardless—he’s always the character I think with and through when I spend time in this world. But when a story directly offers me his view on the plot, and his teammates, and what it all means, rather than making me work for it—that’s special. That’s like the storytellers reaching through the page to acknowledge me.

But in any X-Men comic, a single mutant is rarely the point-of-view character for long. Kurt does some other cool things in this issue, but the rest of the comic is dominated by other characters, faced with their own perfect traps inspired by their own powers and psychologies (and the intrinsic connection between those things). And that’s fine. More than that, it’s how it should be.

The wonderful multiplicity of X-Men comics is located within each character and within the relationships between characters and their many ways of being in the world. This multiplicity becomes magical when creators care so deeply about each character, they can tell a whole story about one of them in four short pages and still have it feel satisfying. When you trust the storytellers, you have faith—that even if your favorite mutant disappears, they’re bound to reappear. And when they do, it’ll matter. If the scene involves Nightcrawler and Dave Cockrum drawing him, it’s a pretty safe bet it’ll also be amazing.

Anna Peppard

Anna is a PhD-haver who writes and talks a lot about representations of gender and sexuality in pop culture, for academic books and journals and places like Shelfdust, The Middle Spaces, and The Walrus. She’s the editor of the award-winning anthology Supersex: Sexuality, Fantasy, and the Superhero and co-hosts the podcasts Three Panel Contrast and Oh Gosh, Oh Golly, Oh Wow!