In 1989 DC Comics released Hawkworld, the last of its big post-Crisis reboots and origin stories, written and drawn by cartoonist Timothy Truman. The three issue miniseries told an origin story for the post-Crisis On Infinite Earths version of classic hero Hawkman while incorporating the gritty urban realism seen in books like “Batman: Year One,” The Question and Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters, the last of these written by Hawkworld editor Mike Grell. Truman’s reboot applied the cynical Post-Crisis style of these books to the alien world of Thanagar, home to the superheroic Hawkman and Hawkgirl. Despite its trendy nature, Hawkworld was very nearly the most radical reinvention of DC’s post-Crisis era, a meditation on American empire and political violence, but the ways in which it faltered in this reinvention and was eventually forgotten, buried under an avalanche of conflicting retcons, are illustrative of the limitations of the superheroic genre and worth unpacking.

Hawkman, in his various incarnations, had long been a DC Comics stalwart. First introduced in the Golden Age as Carter Hall, Hawkman was one of the legion of lantern-jawed adventurers who spent the 30’s and 40’s stumbling upon magical artifacts and scientific formulas and becoming endowed with fantastical powers which would immediately be applied to fighting injustice. As DC moved into the Silver Age and characters like The Flash and Green Lantern were reinvented with a slick sci-fi finish, writer Gardner Fox and legendary artist Joe Kubert saw to it that Carter Hall was replaced by Katar Hol, a policeman from the alien world of Thanagar who moved to Earth and fought crime. Though never an A-lister, Hawkman and his partner Hawkgirl stuck around the DC Universe as perennial guest stars and team members, thanks in no small part to the memorable visual of folks with big ol’ wings.

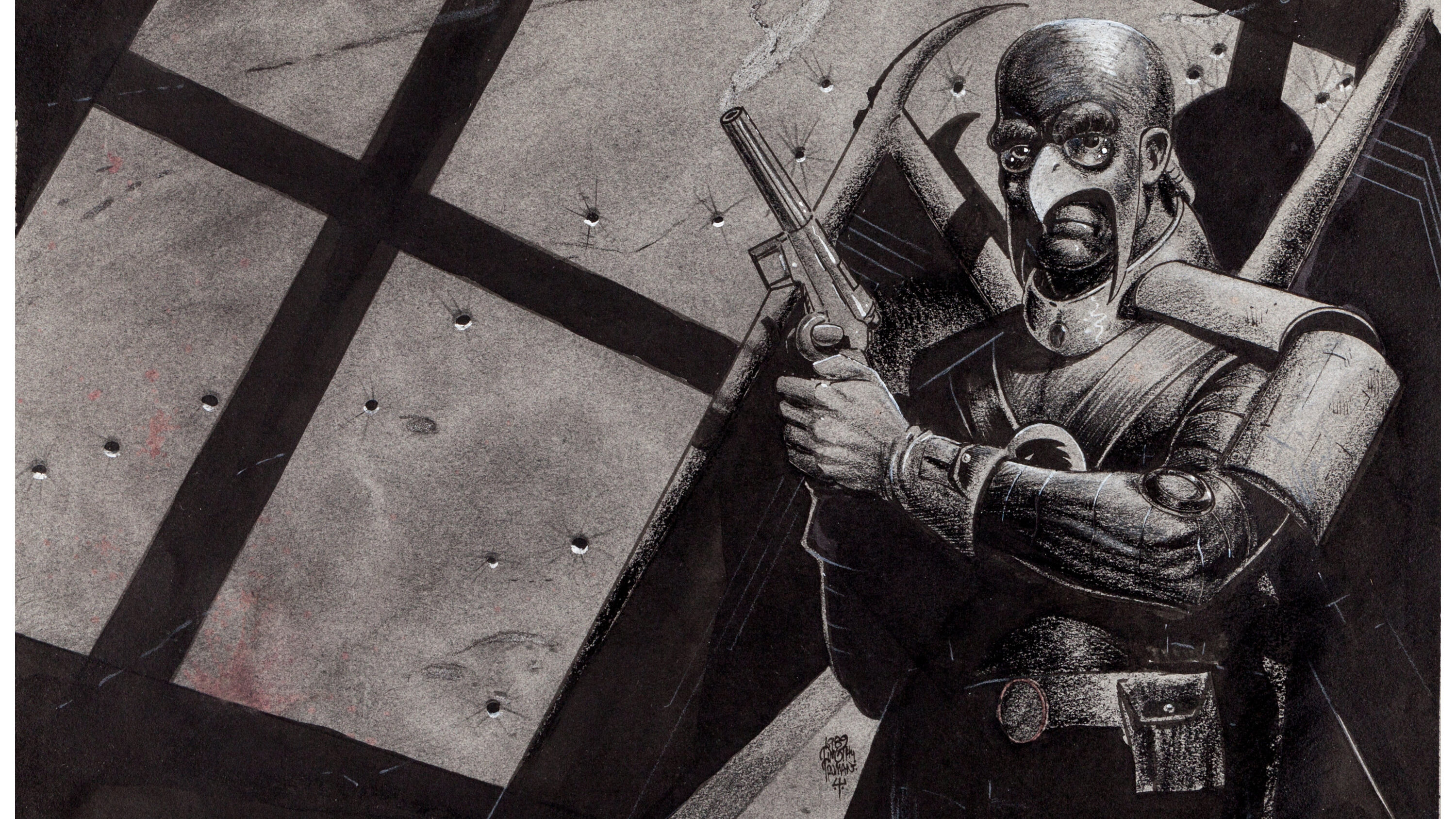

Truman’s Katar Hol, the man who would become Hawkman, is not your daddy’s Hawkman (well, considering the publication date, he probably is, but bear with me). Gone is the Justice League’s resident right-wing stick in the mud. In his place, Katar Hol is a son of privilege slumming it as a police officer in Thanagar’s violently repressive police force, an idealist who pines for the ideals of Thanagar’s mythic past while popping pills to deal with his guilty conscience. He’s not alone; Hawkworld‘s first two issues devote a great deal of time to subverting expectations. Visually, Truman’s painterly style contrasts the retro-sci fi stylings of the classic Thanagar, with military hardware visibly influenced by the real world, and a level of a grime which suggests the nasty side to even the most privileged spaces of this seeming utopia. Hawkgirl is reinvented as Shayera, a belligerently racist aristocrat killed partway through the second issue, and Thanagar itself is far from the utopia rendered by creator Gardner Fox, but instead a crumbling empire built on the backs of the millions of exploited colonial subjects. By the end of the second issue, Katar Hol has been tricked into murdering his own liberal-minded reformer father, banished to a penal colony for ten years, and returned as an ex-convict left to languish in Thanagar’s ghettos.

Thanagar is an allegory for America, and not a subtle one. The opening of the story makes this clear, with a somewhat cheeky introduction noting the uncanny similarities between birds and humanoid species across planets, which not only hangs a lampshade on the fact that Thanagarians are virtually indistinguishable from humans, but also plants the idea for readers that even though this series isn’t set on Earth, in America, the systems it’s depicting are common and recurrent ones.

Thanagar (read: America in 1989) is a creaking empire where production and invention has been outsourced to its colonial holdings, as Katar Hol repeatedly laments.

The upper crust of Thanagar is attended to by an army of abused and deferential servants pulled from its conquered holdings. These visibly alien migrants are imported to the homeworld to toil in obscurity before being cast aside to live in ghettos heavily patrolled by Thanagar’s repressive and wildly militarized Wingmen police force, where protest is quashed and the relief funneled to citizens inevitably co-opted by bad actors. Hol’s own father is the only reformer we see among the Thanagarians, and he is assassinated by the police for his trouble.

Even today the blunt metaphor of Thanagar would be shocking. After all, the events of DC’s recent Future State event and its “Fear State” prequel in the pages of Batman purport to have Batman facing off with corrupt and fascistic police forces, but in these stories he technically fights The Magistrate, a private police force which has taken over for the blameless GCPD, who remain a group of Good Cops. Even in the 2020’s, after years of anti-police protests and activism, Hawkworld‘s politically repressive and openly thuggish space cops would be unusual subject matter for a mainstream superhero comic, perhaps even more so than they were in the 1980’s. Thanks to using Thanagar as a stand-in for America’s ills, from racism to police violence to colonial exploitation, Hawkworld is able to be indirectly direct in its criticisms of American empire.

BUT.

Hawkworld was almost the most radical book of 1989, but why only almost? Why is Hawkworld all but forgotten, rather than an ACAB icon decades ahead of its time? The answer comes in the third and final issue of the series, where the promise of the previous installments is neatly packed away and set aside in favour of table setting for the ongoing series. Where previous issues were unrelenting in their portrait of Thanagar as institutionally flawed and Hol’s idealism was challenged at every turn, the final issue backpedals. Thanagar’s problems come to be embodied solely in Byth, Hol’s former superior officer, a corrupt cop and arms dealer, the man who tricked Hol into killing his own father before sending him to prison. Between the second and third issues Byth has begun using a potent drug which allows him to shapeshift into a big monster and eat his underlings. In case you couldn’t guess, the nuance fades rapidly throughout this third issue.

Shayera the dead racist is replaced with Shayera the alive policewoman, an orphan creepily adopted by the first’s father and renamed in her honor, grown up to be a certified Good Cop, an ally to Katar Hol and the new Hawkwoman in the subsequent Hawkworld ongoing series written by John Ostrander with Truman co-plotting for the first nine issues. Katar Hol is transformed from a broken and disillusioned idealist to a community organizer who’s pulled the non-human community together around him, using the drug trade to finance medical care. The issue makes quick mention that Hol is only organizing the institutions which already existed in the community, but we don’t get any glimpse of this, we see only Katar Hol, the enlightened liberal, saving the abject and largely nameless downtrodden from both themselves and the forces which would prey upon them.

The series finishes in an oddly rushed manner, with Hol confronting the corrupt Byth, who is now, I remind you, a big shapeshifting monster, in a swordfight, after which Byth escapes and Hol is reinstated to the police force and partnered with Shayera II, setting up the subsequent Hawkworld ongoing which would see the pair commuting between Thanagar and Chicago. Systemic concerns are all but forgotten in the rush to resolve the series with a recognizable Hawkman triumphing over a simple villain and set up a status quo for the ongoing series which matched up with DC’s other titles. Where previous issues underlined Thanagar itself as corrupt and broken, the finale of the story focuses solely on Byth, the lone bad actor who can be satisfyingly dealt with in the pages of a pulp superhero narrative.

The final pages of the story leave us on an ambiguous note: As the presumptive Hawkman cruises through the sky with his partner, he muses on how he has already been integrated back into the state and what efforts he can make towards reform are stumbling and small, he reflects with the final words “Our world likes its heroes”

What are we to make of these words? Is this self-recrimination on the part of Truman that the ambitious nature of Hawkworld was ultimately incompatible with the goals of an editorial department mostly concerned with fleshing out a superheroic C-lister’s backstory in line with recent publishing trends? An admission that even in an allegorical setting like Thanagar the superhero framework isn’t truly equipped to address systemic problems?

There’s no real answer, of course. For me, Hawkworld is a fascinating but ultimately frustrating artifact; one which comes achingly close to being extraordinary, only to revert to tired convention in the home stretch. Maybe Hawkworld , or at least the Hawkworld that lives in my head, was too good for our fallen world, its themes too large to be explored in an industry dominated by the often conservative impulses of power fantasy; a squandered opportunity. The subsequent Truman/Ostrander Hawkworld ongoing continued the themes of the miniseries, with Hol and Shayera sent to Earth as ambassadors but largely abandoned the Thanagar/America allegory in favour of dealing directly, and rather mildly, with America. While the disconnect between American ideals and contemporary reality is highlighted, Ostrander/Truman either can’t or won’t condemn America in the same way that Truman could Thanagar. Not only is the imperial critique of the in the miniseries entirely absent in their initial joint run, the main contrast highlighted between Thanagar and America is in their police, with the latter emphasizing due process and the inalienable rights of all citizens to an extent which would have been rich even decades before the age of Defund the Police. Elements of critique which in the miniseries seem shocking in their boldness only become more so when contrasted with the limp criticisms of the ongoing. The ongoing succeeds primarily in highlighting the abortive potential of Truman’s miniseries: Katar Hol never needed to leave Thanagar to learn about America: he was already there.