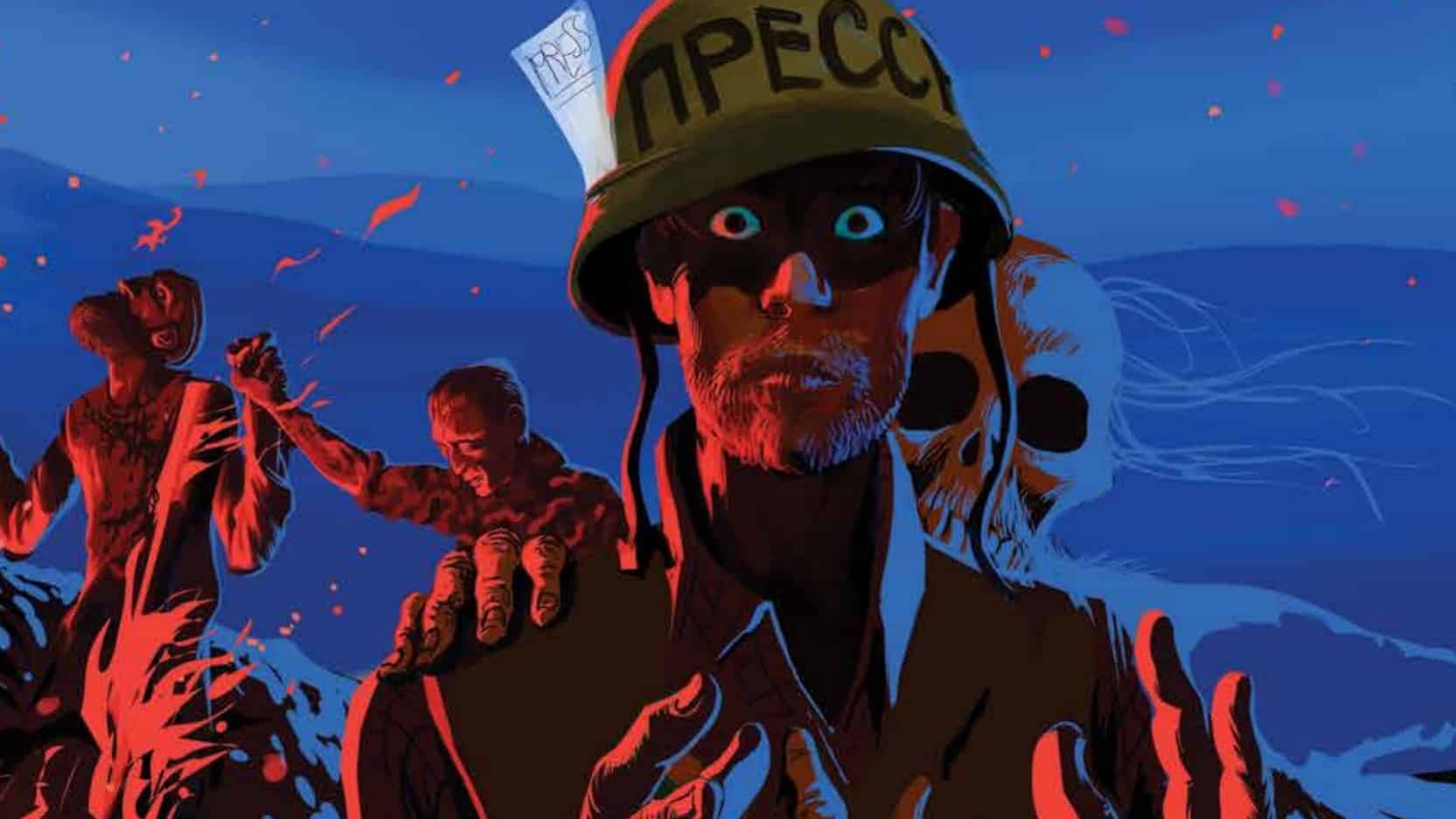

The war rages on! Krylov, now embedded with the Iron Star’s forces, sees the brutality of battle up close. Can he make it out alive with his sanity intact? 20th Century Men #3 takes us from the deserts of Afghanistan to the U.S. capital, and all the way to Mars, courtesy of writer Deniz Camp, artist S. Morian, letterer Aditya Bidikar and publisher Image Comics.

Sean: It was perhaps inevitable that a series like 20th Century Men would slow down. If not for simply the insubstantial nature of raw, unbridled anger, then for pacing. That isn’t to say the issue is bad, but rather it’s not the sort of issue where you see something like The Lion. It’s still an angry book, but it’s a more subdued anger than the previous issue. And, if I’m being honest, a little bit sadder.

Ritesh: It pulls back, as it were, to let us sit with and simmer in a more focused perspective with Krylov. It’s a bit less sprawling compared to the other two, and it makes us feel like we’re sitting in that camp, like we’re walking that desert, right with him. We’re in the journalist’s position, like we’ve accompanied him on the trip.

Sean: In the previous two issues, we’ve been mostly seeing things from Platonov’s point of view. And Platonov is an older man than Krylov. He’s seen the horrors and evils of the world. He’s known The Lion and all his predecessors. He’s seen the dream come to ash and ruin.

Krylov, meanwhile, is still young. He hasn’t seen all the horrors of the world. He isn’t broken with the only potential way forward to dive headlong into anger and fury. He can be sad about the failures of the world.

Ritesh: And beyond that, he’s new to war. He’s new to all the little touches and mechanics and flourishes that make up this place. He doesn’t know its many dances. He does not know how to put on a parachute. He knows not to never ask for food, for the price he inflicts in doing so upon those compelled to offer is all too high. He gets to be the man who has all the “firsts” that shock and surprise. He compels a more visceral and emotional response, given it’s what he feels, as opposed to Planatov’s cold, restrained demeanor. He’s the uncertain, questioning youngling in a den of hunters, predators, trained to kill. He’s the guy trying to make meaning out of mess, where there perhaps may be no meaning at all.

Sean: In this regard, perhaps the most brutal part of the issue isn’t Krylov’s survival of the harsh desert or the implications of the fight they engage in. But rather, it’s the failure of the dream.

Specifically, the space race. One of the more public and famous aspects of the Cold War was the Space Race. A story about two nations trying to see who could liberate the stars first. As with the rest of the Cold War, there were a lot of horrors involved with their conception of liberation and rarely a thought towards those who needed to be liberated.

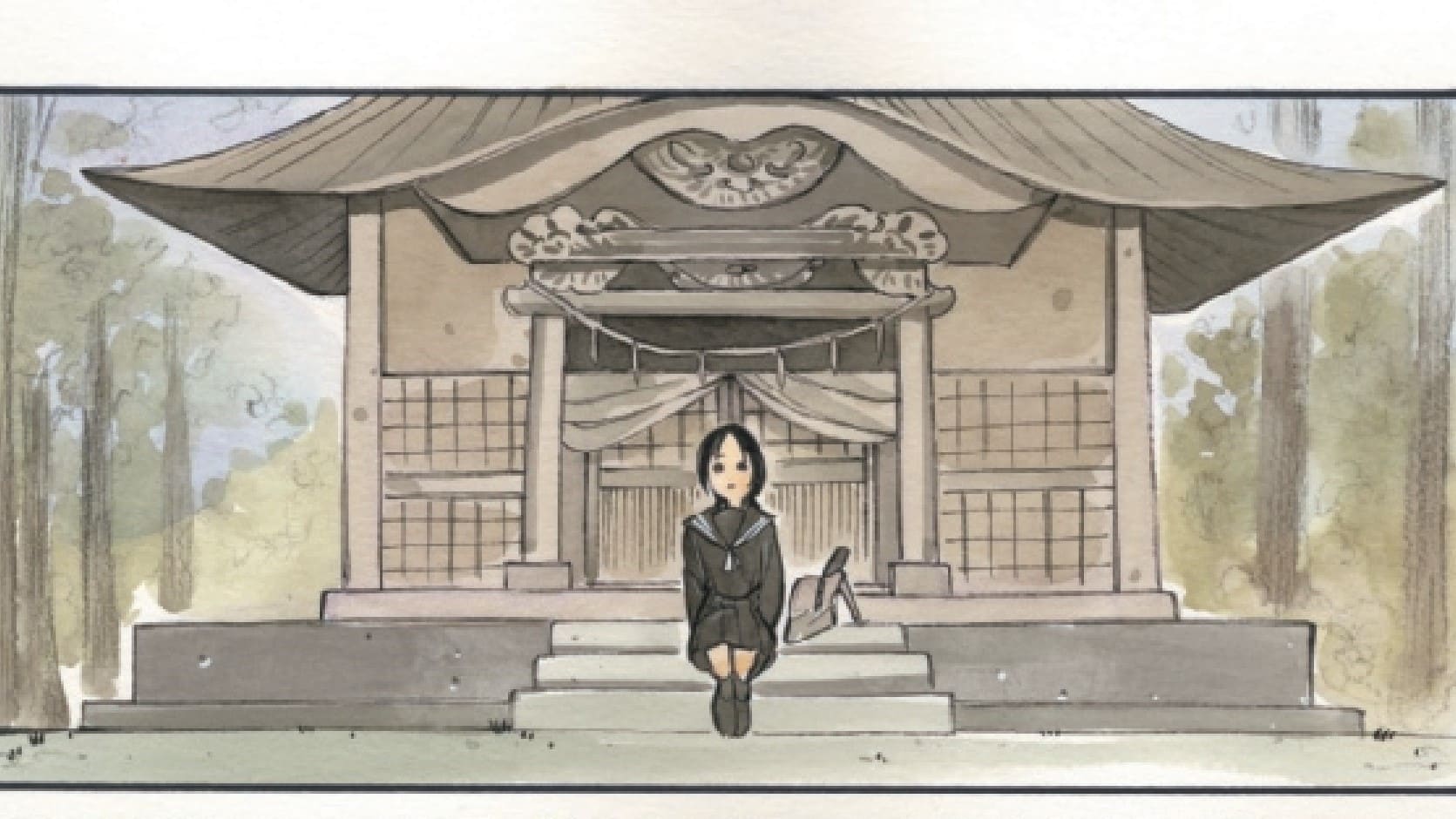

We are shown a propaganda video advertising the Soviet Martian Colonies. How they grew tomatoes on Mars. That there is, indeed, life on Mars. Or, rather, there was.

As with all the plans from the Cold War, the space program got scuttled when the money ran out. The people left on Mars were abandoned. We never see what happened to them. Whether they starved to death, thrived or escaped somehow.

We can hope that they survived, even as we know they’re probably dead. The world is rarely kind to aliens.

Ritesh: And we’re not even fully sure if this is all real or just propaganda they made up that people now just believe. “What is truth?” a man asks, and it rings loud and heavy, in the horror of all its implications.

But leaning into the narrative of it, if it is true, it is a horrific display of the actual concerns of the people that rule. Those that say their nation rewards and takes care of its own, its own loyal subjects, that it’s all something … more, this nationalism and larger ideology that unites.

You just see their bullshit laid out clean and clear, yeah? They care not for dreams, of possibilities, of people even. They care about profit, image and how they serve their power. They care about these meaningless things for which they are willing to let their own die in the cold void of the stars. And it is why they are willing to send all these men off to Afghanistan to die without a care. It’s all about profit, power and image.

And men will do much to maintain and safeguard them.

Sean: In this regard, it’s best to look at the source of the quote “What is truth?” As the issue indicates, it comes from the Bible, specifically, John 18:37-38:

“Pilate therefore said unto him, Art thou a king then? Jesus answered, Thou sayest that I am a king. To this end was I born, and for this cause came I into the world, that I should bear witness unto the truth. Every one that is of the truth heareth my voice.

“Pilate saith unto him, What is truth? And when he had said this, he went out again unto the Jews, and saith unto them, I find in him no fault at all.”

In context, Jesus is being tried for, well, being a rabble rouser who is doing things the Roman rule simply does not like. The truth Jesus is speaking of — of which Pilate questions — is not that of something that can be debunked using facts. Not something that can be proven directly. Rather, it’s an emotional, spiritual truth about the nature of existence itself. That there is more to life than simply this.

As has always been the case, asking for a better life has always been looked down upon by those who have a better life than you. The union man trying to get a decent wage and some medical care is demonized as being corrupt and in the pocket of criminals. The anarchist fighting against fascism is seen as no better than the fascist. And don’t get me started on what people have slung at those who would dare ask for better while working within the “proper channels” as opposed to being like Jesus and openly rebelling.

Ritesh: Yeah. It’s a striking invocation in a comic that is all about these oppressive systems and the monsters they manufacture and how they devour us all in the end.

The scene where the Giant asks Krylov, “You’ll make me a hero, won’t you?” really sticks with me. It’s such a simple thing. A man wanting to be remembered. A man wanting to mean something. A man seeking purpose and romance at least in the realm of narrative, for there is so little to be found in the bloody battlefield all around him. And when Krylov tells him he’ll make him a person instead, which is much better, the Giant responds that, well, regardless of how he comes across or is presented in the book, he just wants his story to reach his mother. He wants Krylov to send her a copy of the write-up. Even if he meets his end here, or rather, not an if, but when he meets his end here, he hopes it will not be his true end. That he will live on in memory, in narrative, somehow, someway, rather than lost to the annals of time, the way those Russian pioneers during the space race were. That his presence and life will not be buried and secret. He’ll have lived. And people would know it. He would not be erased; that had to count for something, surely?

Sean: And yet…

The invocation of Jesus in a Cold War story without Americans is interesting. Speaking as a member of that group, I long grew up on the various stories of Jesus told by the people around me. How he believed one should love thy neighbor. How we should turn the other cheek. How the homosexuals are a deviant race that should be exterminated. How the war in Iraq was part of His will.

All these stories about Jesus are as fictional as the ones I would learn of later in life. It’s a story, but as with all things in this life of ours, it can be corrupted for monstrous deeds. We know so very little about the historical Jesus, what he was truly like, what he did with his time off. What did Jesus find funny? We barely know the guy, and we have done monstrous things in his name.

We have the story of Jesus, certainly. But the real Jesus was lost. We only have the word Jesus. For a man like Giant, we don’t even have a name. Just an affectionate nickname that could be applied to someone large. In 20,000 years, they might think Krylov was Giant. One is not remembered simply by having one’s name spoken. Rather, it’s by having one’s true story told.

But then … what is truth?

Ritesh: Yeah. And it is warpings of actuality like that which in the end power so much here. The idea that those warpings are done by humans, and humans have agendas. The narratives we’re fed and the interpretations constructed express something — they tell us something. And it is the basis of how propaganda works. It’s how imperialism is fueled and justified. It’s how othering and genocide are defended. It’s the utter and absolute disregard for any kind of truth at all, which actively dehumanizes an entire people, that justifies the might and divine superiority of one people over another.

It is how this whole business — and make no mistake, it is business — is conducted. It is a sad thing. It is an ugly thing.

Sean: “I look for truth, and find that I get damned.

But what is truth? Is truth unchanging law?

We both have truths.

Are mine the same as yours?”